I have two copies of the History of Plain City, Utah. The front indicates it is from March 17th 1859 to present. As far as I can tell, the book was written in 1977. At least that is the latest date I can find in the book.

One copy belonged to my Grandparents Milo and Gladys Ross. My Grandpa has written various notes inside the history which I intend to include in parenthesis whenever they appear. They add to the history and come from his own experience and hearing.

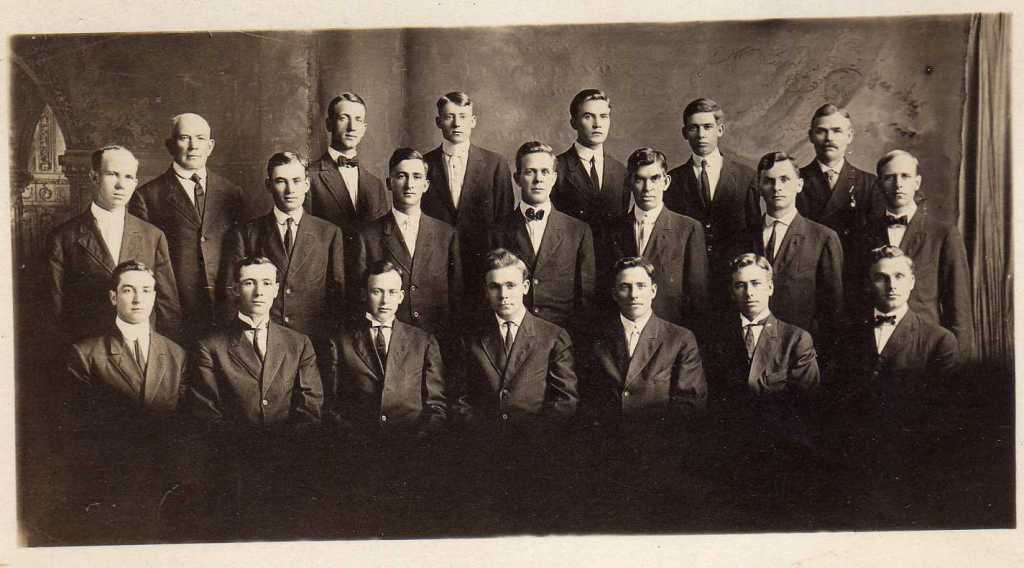

I will only do a number of pages at a time. I will also try to include scanned copies of the photos in the books. These are just scanned copies of these books, I have not tried to seek out originals or better copies.

History of Plain City March 17th 1859 to present, pages 1 through 32.

Preface

This history was compiled and printed for the purpose of supplying some facts, stories, and histories of the town of Plain City. That you as an individual may take a little more pride and stand a little taller in the support you give our town. It is a tribute to the men and women who had the foresight, vision, courage, and strength to endure the hardship that were necessary to make Plain City a nice place to live.

They were a choice breed of people selected to perform great and noble deeds. Their character was unselfish and pure. Their word was their bond. Their ambition unmatched, and their courage unequaled. Their convictions were true and they were a happy people.

We encourage you to read the entire book for we think you will find it enlightening and interesting. We know that this is not a complete history of Plain City, but we used most of all of the material that was turned in. We realize that there are duplications, grammatical errors, dates that conflict, and others, but please don’t pick away at the format so much that you miss the important message. If any are dissatisfied, we issued a simple challenge; collect and write your own history.

It is not the intent of any of the articles to show malice or unkindness to anyone. But, rather we encourage any and all to look upon it as a tribute to an already good name.

We should extend a special thanks to the Plain City Community School, and especially to Robert P. Stewart, Principal. Bob thinks and acts like a native of Plain City, and his helpful knowledge in putting the book together is appreciated. His help and cooperation in getting the book to press were invaluable.

Ruth Powers, whose ideas and work have helped to make the book all possible. Her concern for the total book, and her work in collecting materials is most appreciated.

Clara Olsen and Roxey Heslop have collected and written articles and helped to put the book together. Their work is appreciated.

My good wife Dorothy, whose background and training in editing has been most helpful. For the ever long hours we have worked together has been enjoyable. As we go to press, the hours worked seem short, the rewards great, and the satisfaction elevating to say the least. The most rewarding experience have been with the people who welcomed us into their homes and supplied us with pictures and materials. We are most appreciative.

And, to any others who have helped in any way with the book, we appreciate them.

Lyman Cook

Dorothy Cook

Editors

TABLE OF CONTENTS

History from the Daughters of Utah Pioneers, Plain City Camp . . 1

Latter Day Saints Church History of Plain City . . . . . … . . . . . . . . 33

Mary Ann Carver Geddes . . . . . . . . …. . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . .. . . . . . . 44

Early Settlers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

History of the “Dummy” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

Agenda of the First 17th of March Celebration, Fifty years in P.C. 53

12th Annual Homecoming Article . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54

Collection of Histories, stories, etc. of early Plain City from many sources 55

Documents of Servicemen’s Monument . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79

Beet Growing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 83

Dairy Days . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . .. .. . . . 86

Cemetery . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91

Plain City Town Incorporation, Town Boards, and Mayors . . . . . . . . . 95

Lions Civic Center . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 105

Schools . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107

Sports . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 123

Bona Vista Water, Plain City Irrigation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . 141

Town Park . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 150

Story “A Child’s Christmas In Utah” By Wayne Carver . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 151

Pictures of Early Plain City . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 156

Business of Today . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 161

Can You Remember or Did You Know, by Lyman H. Cook . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 166

PLAIN CITY HISTORY WRITTEN BY AND IN POSSESSION OF DAUGHTERS OF UTAH PIONEERS, PLAIN CITY CAMP

Plain City is located about 10 miles northwest of Ogden, Utah.

In the fall of 1858, a small group of Lehi men went north into Ogden and vicinity for the purpose of locating a site for the founding of a new settlement. Conditions in Lehi at this time were not very encouraging for the late comers. The water had already been appropriated by the early settlers. There was no range for the cattle, not much good farmland left, and other adverse conditions which made it necessary for the late comers to seek homes elsewhere.

During the general exodus south in 1858, many Lehi men contacted farmers from Weber County who told them of the rich lands lying to the west and north of Ogden. They decided to go there and locate farms, if the conditions were favorable.

One of their camping places was on Kay’s creek (now Kaysville), near the farms of John Carver, John Hodson, and Chris Weaver. As conditions here in Kay’s Ward, respecting the priority of water rights were similar to those in Lehi, John Carver decided to join them in their expedition north. John Hodson went to Plain City later. This was in October of 1858.

Their next camping place was at the intersection of Twelfth Street and Washington Boulevard in Ogden. There they met Lorin Farr, who had just returned from the rich plains northwest of Ogden, where he pastured his cattle. He told them he thought it would be an ideal site for a settlement, as water was not far away and the soil was very rich and deep. They decided to look over the country with Lorin Farr acting as guide. Among those in the company were Daniel Collett, Joseph Skeen, and his son William, Thomas Fryer, W. W. Raymond, John Spiers, Joseph Robinson, John Folker. Joseph Folkman, Jeppe Folkman and Thomas Ashton.

(Statements of Lyman Skeen, Thomas Fryer, and Willard C. Carver, Deweyville, Utah April 22, 1919. Copy of Thomas Fryer’s statement obtained by Robert Davis.)

I was one of the party that came up to where Plain City now stands in the fall of 1858. We camped where the big levee was made, a party consisting of Joseph Skeen, Collet Hopkins, David Francis, Thomas Frayer, Robert Maw, and others with Mr. Garner who lived on Mill Creek near where the Slaterville Creamery now stands (1919).

With Mr. Garner as guide we followed up Mill Creek to where Mill Creek crosses Twelfth Street. From there with a level made out of sixteen-foot two-by-tour, grooved out by this same Mr. Garner, and set on a three-legged tripod, with water in the groove to act as a level, from this joint as described on Twelfth Street, the Plain City Canal from this joint to “Big Levee” was made.

The preliminary survey was made by Mr. Garner. The tripod was carried by William Skeen and myself. The water to fill the level when it was rested was carried in a canteen by Joseph Skeen. This preliminary survey was made to the Big Levee that fall of 1858. We worked on the Big Levee that fall till we went back home to Lehi. In March, 1859, we moved to where Plain City is now established.

In the Spring of 1858, Joseph Skeen brought Jesse Fox to Plain City after the first settlers came to Plain City and he re-surveyed the canal over. The preliminary survey was made by Mr. Garner and after that we went back and made a survey from Mill Creek to Ogden River. I came to Plain City with John Draney, Sam Parke, and the Garners; two or three days after the first arrivals.

When we came there was little or no snow on the ground. Two or three days after a snowstorm came. The ground was covered with high bunch grass and sage brush.”

Besides making this preliminary survey of the canal, the little group of men selected their farms and lots with the understanding that their choice met with the approval of the colonists who were planning to come later, cleaned out some of the springs to the west, rode over the pastures land around Little Mountain, and undoubtedly gave some attention to the planning of the location of the village.

Then they returned to their homes to wait until the next spring before moving to the place they and to his home for their future homes. John Carver walked to his home on Kay’s Creek; most of the way through deep sand.

On March 10, 1859, quite a large body of colonists left Lehi to come North and located upon the site chosen in Weber County, the fall before. They were seven days on the trip making seven camps as follows:

- On the Jordon River this side of the point of the mountain.

- Where Murray is now situated.

- Upon the site where Centerville is now located.

- Kay’s Creek, now Kaysville.

- A dry camp north of the sand ridge.

- On the Weber River northwest of the sugar factory.

- Plain city on March 17, 1859.

Part of the company stayed in camp near the present site of the Amalgamated Sugar Factory, but the Vanguards pushed on ahead, arriving about 5:00 pm, March 17, 1859. According to Lyman Skeen’s statement, only about 12 or 14 actually came with the first company.

Upon arrival March 17, 1859, the snow lay deep upon the ground, and the cattle belonging to the company were driven to Little Mountain for feed with Alfred Folker, and Mile Nolan in charge. (By Lyman Skeen)

According to Willard C. Carver all who came in the first group, consisting mostly of those who had teams, made camps on the west side of Plain City, near the spring and started to till the soil. They arrived on the 17th of March, 1859. Then another group came in a little later and camped on the Sam Draney’s lot because it was dry and sandy and there wasn’t room near the other camp as the land was being cultivated

Copy of Robert Maw’s statement dated April 16, 1916 at Ogden, Utah.

I Robert Maw, say that I was on of the first pioneers who came to Plain City on March 17, 1859. We left Lehi on the 10th of March, and was 7 days on the road. Crossing the mud flats at Bountiful, we had to hire extra teams to pull us through. We got to Plain City about 5 o’clock in the afternoon and we camped on Samuel Draney’s lots in a little hollow in the south part of what was afterwards Plain City Plat. The sage brush was very high there. We piled up sage brush behind the wagons which we had lined up east and west and that protected us from the north wind. We dug a big hold in the ground and built a big campfire on the south side of the wagons, and made a very comfortable camp.

In crossing “Four Mile Creek” we had to double teams because the frost was nearly all out. We had 6 to 8 oxen on the wagon. I drove one wagon and in our wagon was Thomas and Mary Davis, Deseret Davis Masterson, Mary Davis Skeen, and my wife, Ann Davis, to whom I was married in Lehi before we came to Plain City. After we left Four Mile Creek we found patches of snow here and there and the ground was very muddy, no roads. On the night of the 19th, it snowed about 10 inches.

List of Plain City Pioneers of 1859, as given by Robert L. Davis and revised later by Peter M. Folkman, Josiah B. Carver, and others.

George Musgrave and wife, Victoria Dix

Charles Neal and Wife, Annie England

Jens Peter Folkman and wife, Matilda Funk and son, George P. Folkman

Robert Maw and wife, Ann Davis

Jeppe G. Folkman and wife, Annie

Thomas Davis and wife, Mary, and the following children:

Mary Davis

John Davis

Robert Davis

Deseret Davis

Joseph Robinson and wife, Alice Booth

Susannah Beddig came 23 of July, 1859

Seth Beddis

William Sharp and wife, Mary Ann and the following Children:

Elizabeth Sharp

Evelyn Sharp (born in Plain City in 1859)

Lorenze Padley and an adopted son or stepson

William VanDyke and wife, Charlotte and son William.

David Francis

Daniel James and wife and the following Children:

Charlotte Ann

Elizabeth Ann

They stayed only a short time and went to North Ogden.

Came in the fall of 1859

Alonzo Knight and wives, Catherine McGuire and Martha Sanders

William Knight

Charlotte Knight

Amanda Knight

Henry Newman and wife and the following children:

Henry Newman Jr.

Deseret Newman Jr.

William Skeen and wife, Caroline and son William Jr.

John Folker and wife, Alice and son Alfred, who rode horse back with Lyman Skeen and daughter Anni Folker.

Joseph Skeen and wife and following children:

Joseph Skeen

Lyman Skeen

William Skeen

Jane Skeen

Moroni Skeen

Thomas Singleton and wife, Christine Woodcock and the following children:

Elizabeth Singleton

Emma Singleton

Sarah Singleton

Thomas Jr. The first born in Plain City that year.

John Draney and wife and the following children:

Samuel Draney

Isabel Draney

Jonathan Moyes and wife, Dinah Abbott

James Rowe

William Geddes and wives, Elizabeth and Martha

Agnes Geddes

William Geddes

Joseph Geddes

Hugh Geddes (born in Plain City in the fall of 1859)

William L. Stewart

Abraham Brown and wife and the following children:

Jeanette Brown

Byron Brown

Newell Brown

Oscar Brown

Leveridge or Leavitt Brown

Clinton Brown

Christopher Folkman and wife, Elea and son George D.

Daniel Collet and wife, and the following children:

Ruben Collet

Charles Collet

Matilda Collet

Julia Collet

Samuel Cousins, mother, sister

Ezekiel Hopkins

Daniel Hopkins

John Spiers and wife, Mary Ann Winfield

Martha Spiers

Alberta Spiers

Winfield Spiers

John Spiers (Came a little later with Martin Garner and wife and children

Tene Garner

Hannah Garner

John Garner and wife and son and daughter

Jonathan Partridge

John Carver and wife, Mary and the following children:

Mary Ann Carver

George H. Carver

James S. Carver

Thomas Ashton

John Draney Jr.

Thomas Brown and wife

Clint Brown

Hans Petersen and wife and son August

John Beck

Clint Brown

Hans Petersen and wife and son August

John Beck

Leavett Brown

Came in 1860:

Alonzo Raymond and wife and children

Lori Raymond

Mary Raymond

Ida Raymond

Susannah Raymond

William Wallace Raymond and wife, Almira

Spencer Raymond

William Raymond

Mina Raymond

Seretha Raymond

One of the first things they did after arrival was the survey the townsite and assign the lots to the settlers so they could get some kind of shelter for their families.

Joseph Grew states that John Spiers and others who surveyed Plain City had in mind the old home, the city of Nauvoo, and followed the pattern as nearly as they could.

They surveyed the town at night using the north star, and three tall trees just below it as which they waded.

The original plat was six blocks long and three blocks wide running north and south. Each block contains 5 acres and is divided into four lots. Each settle was allowed some choice in the selection of his lot.

The Central St. Was from Alonzo Knight’s corner running north to Robert Maw’s old adobe house. There was one street each side of this running north and south. The “Bug field” or farming land one mile square lay to the east of the town site extending from the cemetery corner and north to the old north school house.

The old Joshua Messervy place was on the east line. There were three main gates; one by George Palmero, and one by the old north school house. Each settler was allotted twenty acres of farmland. As soon as the crops were gathered in the fall, the community was notified, usually from the pulpit on Sunday afternoon, that the stock would be turned into the “Bug Field” upon a certain date and everyone who owned land turned his stock in to the field on the day. One long willow fence enclosed the whole field. The willows used in the construction of all willow fences in Plain City were brought from the Weber River, south of the settlement. The outside of all or nearly all the lots ion Plain City at this time were thus fenced.

There were no partition fences then. Chickens and hogs roamed at will within the fenced blocks. In fencing, a trench was dug having all the dirt piled along one side, into this bank sharp stakes were driven and the green willows woven in and out through them to make a fence.

The following from Lyman’s Skeen’s notes. “There was no feed except such as the stock could gather, and as rapidly as possible small areas were grubbed, plowed, and planted. When a part of the crops were planted John Skeen went to Salt Lake and secured the services of Jessie M Fox, the pioneer surveyer who laid out Salt Lake City, to run the irrigation ditch line to “Four Mile Creek.” It is worthy to note here that while Mr. Fox also ran the lines for the town, he did not change the original lines that were made by the North Star and the rope by the pioneers upon their arrival. Work was commenced upon the irrigation ditch. In the meantime, those men who had not moved their families from Lehi returned to get them. The harvest of 1859 was light, it being possible together but very little, such as corn, squash, and some potatoes, and very little, wheat, which was threshed by flail or sticks. The lack of teams, implements, etc. , limited the acreage planted, and due to the lateness of the season when the irrigation ditch as far as Four Mile Creek was completed, the crops did not mature properly. Because of lack of water, no hay was harvested in 1859. The stock was driven to Little Mountain in the late fall to winter. In the spring of 1860. it was necessary to hold back farm work until the stock could gain strength on the spring feed.”

“Becoming discouraged by the experiences of 1859, some of the settlers went to Cache Valley. Among them being Ruben and David Collett, Samuel Cuspins, Ezekiel Hopkins’ mother and sister, and Mr. Lilly. John Falker and Alfred Falker moved to Ogden. Others came from Lehi to temporarily fill the ranks, some of whom later moved to Cache Valley. .” Willard Carver’s statement. “John Carver dug down into the ground he selected with a piece of sage brush. Joseph Robinson, Thomas Singleton, Charles Neal, George Musgrave, Clint Brown, Jeppe Folkman, and Peter Bech camped by Carver’s on Kay’s Creek. They drove on to the sand hills in Wilson Lane on the 16th of march, 1859. John Carver accompanied them as far as Slaterville. He stopped here to get shelter for his wife and children before going on.

Joseph Skeen and two or three others cleaned out the springs below where the Skeens located, while the Singletons, Charles Neal, and Mr. Beck cleaned out those near the spot where Jens Christensen afterward lived.

By the time the second company came, the first company had cleared some land. William Skeen rode a horse sown to Lehi and led another group to the new settlement; his wife Caroline being one of them.

There was deep mud before the heavy snowstorm came. They were almost snowed under. Some started to excavate for their houses the day after their arrival, but didn’t finish them right away, on account of the storms. They got their willows for the roofs from the Weber River about two miles away. My mother, Mary Ann Carver, with her children stayed in a dugout in Slaterville while her husband, John Carver, was building a house and working on his land. He walked back and forth between Slaterville and Plain City. The reason the Carvers and others left Kay’s Creek was because the early settlers of Kay’s Creek would not share the water with them. “ End of Willard Carver’s Statement.

At the time of the settlement of Plain City there were no villages to the east; only the homestead of the Lakes, Taylors, Shurtliffs, Dixons and others. Also, the “Prairie House” or herd house where men stayed who were looking after the “dry herd.” There was another herd house on Little Mountain built before the pioneers came to Plain City. Captain Hoofer’s herd house was the only house between the Weber River and Kaysville at that time. About due east of Plain City where Higley lives now, was located a boarding house to accommodate the stage drivers, emigrants, etc., traveling between California, Montana, and the east. When the woman who ran the place out a stick with a white cloth tied on the end of it, it meant pie or some other treat.

The distance from the corner of the square in Plain City to Wright’s corner in Ogden, was measured by revolutions of a wagon wheel and found to be ten miles.

THE PLAIN CITY CANAL

This is a nine-mile canal connecting the irrigation ditches of Plain City with Ogden River. It was commenced in May of 1859, shortly after part of the crops were planted, and completed to Four Mile Creek that first year, but not in time to save the crops.

In 1860 some water was carried to the thirsty ground and some crops matured, but Plain City, due to its position at the end of the Ogden River system, has suffered extremely through lack of water in dry seasons, although having some of the oldest rights on the Ogden River.

In the construction of this canal the cooperation and persevering spirit of the Plain City people was shown, although their implements were crude, yet they went ahead with determination until they finally got the life-giving water to their fertile soil.

“They used a V-shaped scraper made out of split logs and weighted down with men. Five or six yoke of oxen were used to pull the scraper and horse teams were used on the plows, to break the ground for the ditch work. The dirt was dug out with spades and shovels. The dirt was hauled in wheel barrows from the high place to build up the low places. When they built the big levee, the dirt was hauled to the levee in wagons and wheelbarrows. Large chunks of sod were dug out with shovels and hauled in wheelbarrows. The construction of the big levee was one of their hardest problems.

“When the big levee broke it caused a lot of excitement and men were kept there night and day to watch it. While working on the canal many men only had a piece of black bread or a cold boiled potatoe for his lunch.” (Statement of William F. Knight and Lyman Skeen.)

By 1860, the canal was finished to Mill Creek, by 1861, to Broom’s Creek, and by 1862, to the Ogden River.

Joseph Skeen was appointed watermaster with Ezekeil Hopkins and Jeppe Folkman assistance in May, 1859.

The upkeep of the Plain City canal has been quite high due to the fact that there have been so many washouts on the big levee, and so many law suits with the neighboring villages over water rights.

The Plain City Irrigation Company was first organized according to law on August 18,1874, although it had controlled the canal since it was commenced in 1859.

The completion of the Echo Dam in 1932 has relieved the water situation considerably and a plentiful supply of water is assured for Plain City unless something unforeseen occurs.

On July 16, 1924, the stockholders of Plain City Irrigation Company subscribed for 2500 acre feet in the Echo Dam which was increased to 4,000 acre feet on May 7, 1925.

CULINARY WATER

The first culinary water used in Plain City came from the springs on the west side of the settlement and was carried by the pioneers to their homes in buckets. Thus we find that the oldest houses in Plain city are located along the western edge of the town. It was not long, however, in fact during the first year of settlement, before people began digging open wells which was not a difficult thing to do because there was a plentiful supply of underground water in that locality. Fish were put in the wells to eat the insects.

The next type of well was the square boarded kind with a covered top and a bucket to draw the water in.

Then came the hand pumps, several of which are still in use in the village today. Pipes were driven deeply into the ground and a pump attached which forced the water to the surface. They were placed outside at first, usually near the kitchen door. Then they were placed inside the kitchen with a sink attached. Of late years, several homes have installed electric power pumps which make it possible to have hot and cold running water.

After irrigation commenced in Plain City, a variety of different crops began to be raised. The soil was very productive, so we find the pioneers engaging very extensively in raising vegetables and fruits of various kinds. Some of the crops grown were corn, squash, potatoes wheat, sugar cane, small fruits and later apples, pears, apricots, plums, grapes, melons, and tomatoes.

About 1861, Edwin Dix, a convert from London, England brought the first strawberry plant into Plain City from Salt Lake City. He worked for Mr. Ellabeck, a gardener, in Salt Lake and took part of his wages in strawberry plants which he distributed among his friends in Weber County. The parent stock of these plants was grown in California and brought to Utah by pony express. From this small beginning the culture of the strawberry became one of the leading industries of Plain City. Hundreds of cases were sent out every season to different parts of the country and people even came from Salt Lake to get some of Plain City’s delicious Strawberries.

Mr. Rollett, a Freshman, introduced the culture of asparagus into Plain city. The seed came from France in 1859. This, too, became one of the leading industries of Plain City, as the soil and climate were especially adapted to its culture. Several had small patches at first and carried it into Ogden to the grocers, and dealers also peddled it from house to house in Ogden. It was also sold to Chinese Market gardeners who came out from the city in search of asparagus and rhubarb to augment their own products which they sold from house to house.

Plain City asparagus, like Plain city strawberries, has become known far and near. At the present time there are several large patches in the community which furnish employment to many people during the season. Most of the product is handled at present through the Asparagus Growers Association.

Corn and grass were used for stock feed before the introduction of alfalfa which was brought to Utah and California by the early settlers and has been of great benefit in building up another thriving industry of Plain City dairying and stock raising.

The sickle, scythe, and the cradle were some of the early implements used in the harvesting of grain. Women usually gleaned in the fields after the reapers.

Plain City at one time was called the “garden spot of Utah” because of its wonderful vegetable gardens and fruit orchards.

At one time, there were many cottonwood trees in Plain City, but the trees were cut down as the cotton fell upon the ripening strawberries and rendered them unfit for the market.

Nearly all the early residents of Plain City raised enough gardens stuff to supply their own tables. Some, as has been previously stated, made a business of gardening and marketing their produce in Corrine, Ogden, and Salt Lake and other nearby cities. Many of them sold their produce to L. B. Adams, who was one of the pioneer shippers of Ogden and vicinity. Prominent among these early market gardeners were Abraham Maw and wife Eliza.

John Spiers and Edwin Dix were other early market gardeners. They brought a few roots of asparagus from the “states.” others engaged in this business were John Moyes, Mrs. Virgo and Mrs. Coy who peddled vegetables in Ogden and could knit a pair of stocking during the trip.

William Geddes is credited with bringing the first grape vines to Plain City from Salt Lake.

Jonathan Moyes, his son John, Alonzo Knight, Thomas Musgrave, George Musgrave, Jens Peter Folkman, Charles Neal, Thomas Singleton were also engaged in market gardening in the early days of Plain city. Other crops grown were wheat, oats, alfalfa, potatoes and later tomatoes and sugar beets.

Joseph Robinson was one of the first to raise alfalfa in Plain City.

The sugar beet industry is one of the leading industries of Plain City. Prior to the coming of the railroad into Plain city in 1909, the beets were hauled to the Hot Springs and sent by the rail to the Amalgamated Sugar Company plant at Wilson Lane, or hauled direct to the factory. After the advent of the railroad there were beet dumps placed at convenient points along the line for the accommodation of the growers in unloading their beets. The beets were then reloaded upon cars and sent to the factory to be manufactured into sugar.

Before the enlarging of the factory at Wilson, during the month of October, it was necessary to pile the beets by the dump until winter, when they were loaded upon cars and sent to the factory as needed.

Sugar cane was grown quite extensively in Plain City at one time and molasses made from it. There were several molasses mills at one time. One was located where Del Sharp’s barn is now. Petersons had one of the first on his lot where Hans Poulsen now lives. There was also one further south.

In the manufacturing of sugar cane into molasses the stocks were fed into an iron grinding machine which extracted the juice. This juice was then placed in large sheet iron vats holding two or three hundreds of gallons each and boiled down to the consistency of a thick syrup or molasses. Sagebrush fires supplied the heat. The skimmings went to the children to be used in molasses candy. Alonzo Knight had a mill west of William Hodson’s house. John Draney had one on his lot, also one on the lot where George Palmer’s home is. There was also a mill in north Ogden where several of the growers took their cane to be manufactured into molasses.

FOOD OF THE PIONEERS

Several of the wild herbs were used quite extensively for food before the cultivated vegetables came into general use; and it is well to note here that modern science is finding that these same wild herbs contain properties of great medical value. Some of these early wild foods were the sego lily root, nettles, pig weeds, red roots, dandelions, sour dock, etc. Also, wild spinach was boiled and used for greens. Melon and beet juices were boiled down to a thick syrup to be used as a sweetener in connection with molasses. Peeled melon rinds were preserved and considered a great delicacy. Fruits and vegetables of various kinds were sun-dried upon the tops of sheds and stored away in flour sacks for future use; apples, plums, prunes, peaches, apricots, pears, sarvisberries, and wild currants were among the fruits commonly dried. The vegetables were corn, squash, beans, peas, tomatoes, etc. Tomatoes first had the pulp removed and were cut in rings and dried the same as the other vegetables.

Whenever a pioneer woman got ready to dry her fruits or vegetables, she would invite a group of women and girls to an apple or peach cutting, or corn drying, or some other kind of “bee” and they would all have a good sociable time together while working. Afterwards, a little party would be held and refreshments served, usually molasses candy and dried apple pie. The apples were cut into four sections and cooked with the core in.

(M.A. Geddes)

STOCK RAISING

Many of the early settlers of Plain City went with the intention of engaging in the cattle business. It was favorably located for this as the pastures were not too far away, and there was a good summer range available in the mountains to the east and northeast. They brought some stock with them from Lehi. Jens Peter Folkman, John Falker, Mike Nolan were the drivers. The snow was so deep they could hardly get through, as there was no grass available. The cattle had to eat bark from cedar trees for food. This was an ideal place to raise cattle because the range land lay west and east of Plain City. The west range toward the lake could be used in the fall after the mountain range on the east was closed due to snowfall. Some of these early stockmen were Gus Petersen, who raised cattle, sheep, and horses. William Skeen, Joseph Skeen, and his son Lyman raised cattle and horses. Alonzo Knight, his son William, Claybourne, Thomas, James Madison Thomas, all pastured their cattle and horses out at Promotory. William Wallace Raymond had his pasture out west toward the lake. Milo Sharp, the Geddes family, Thomas England, James England, ran their herd out by the “Hot Springs.” They were there in 1869 when the railroad went through.

As there was no feed in Plain City for the cattle, they were driven out to “Little Mountain” on the west to pasture. Each winter the milk cows were dried up and sent out with the beef cattle to pasture. As soon as sufficient water was brought to the settlement to mature the crops so that stock feed could be raised, the milk cows were kept home and milked in the winter.

“I remember one time when the Mormon Batallion was having a party in Plain City. I had to drive my mother to Farr West to get some butter, as there was none to be had in Plain City Prairie Houses.”

These were houses located at different places on the range where the herders stayed during the summer to look after the “dry herd.” One was located on the highway between Ogden and Brigham about due east of Plain City. One was “Little Mountain” which was there before Plain City was settled. Then there was Captain Hoofer’s “herd house” which was the only herd house between the Weber River and Kay’s Creek. This house was 20 by 16 feet. It had a roof of Willows, canes, and dirt, and a large fireplace in one end. There was also another “herd house” located about where Dell Brown now lives in Farr West. Abraham Maw’s was the house farthest north in Plain City. Dave Kay, Lori Farr, and other cattlemen of Ogden at one time pastured their cattle where Plain City is now located. North Ogden also used Plain City as a range.

Most of Plain City herd ground is to the west and north of the town. It was allotted to the settlers at any early date.

Every fall a “roundup” was held and each one went and claimed his own stock which had previously been branded in the spring before being sent to the summer range. The fields to the east were pastured as soon as the crops were removed in the fall. The announcement was made from the pulpit at the Sunday meeting that the cattle would be turned into the fields at a certain date and those laggards who didn’t have their crops out made frantic efforts to harvest them before that date. Where the town of Warren now stands was once pasture land. Alonzo Knight located his wife Martha and family there to look after the herd. She milked cows, churned butter and walked to Plain City to the store with her butter and eggs.

The community herd was taken care of by a herder hired by the owners of the cattle. His duty was to drive the cows to the pasture from the public square and bring them back at night. Mr. McBride was one of the early town herds, although the town herds are a thing of the past.

The “tithing” herd was not taken care of locally, but was sent to Ogden and put in with the general herd there. What few sheep there were in Plain City were herded on the square in summer and fed at home in the winter.

MERCHANTS

Two or three of the earliest merchants in Plain City were A. M. Shoemaker and William VanDyke. The former had a little store just east of where the meeting house now stands. William VanDyke’s store was as just across from the southwest corner of the square. Also, one of the first was Jens Peter Folkman. He had a store where he lived and also a meat shop.

ADOBE MAKING

Joseph Skeen Sr. is credited with having made the first adobes in Utah. He learned the process in California while with the Mormon Batallion and introduced it first into Salt Lake and then in Plain City in 1859.

The adobe yard was west of Plain City just below the hill west of Lyman Skeen’s present home.

The mud was mixed with the feet in pits until it was the consistency of paste or mortor. It was placed by spades into wooden molds holding either two, four, or six adobe. These molds were 4x4x12 inches. They were let dry for awhile and then tipped out a hard dry surface to harden in the sun. In order to loosen the adobes easily these molds were first dipped in cold water and the bottom sanded. The adobes were set together in a building with mortor the same way bricks are. Among those who were engaged in adobe making were Joseph Skeen Jr., John Spiers, William Sharp, Thomas Singleton, Joseph Robinson, Jeppe G. Folkman, William England.

Besides the one adobe yard west of Lyman Skeen’s home, there was one just below Coy’s Hill, one below George Moyes. A community one was out north below Abraham Maw’s near the Hot Springs.

EARLY HOMES IN PLAIN CITY

The first homes were “dugouts” as there were the quickest and easiest made in that timberless and rockless section. These “dugouts” had dirt floors and roofs, a fireplace in one end, and a door and a window on the other. There was no glass at first. Sagebrush was used for fuel, also for light. They were usually about 10 ½ feet by 15 feet. It was necessary to get down steps to get into them. Some were made of sod and dirt, others were made of dirt and boards. The sod was used in the construction of the walls. The dirt floors got so hard in the summer that they could be wiped with a wet cloth. There were cupboards built in the side of the walls. By digging into the earth, steps were made level. This was where they put their dishes. A bake oven hung in the fireplace. The roofs were made by first covering them with cottonwood timbers and willows from the Weber River, then a layer of rushes and a thick layer of dirt.

Charles Neal is credited with the first “dugout” in Plain city, located where Alfred Charlton’s home now is. After the road to North Ogden Canyon was opened up, logs and crude lumber became available for the construction of log houses.

Joseph Skeen built the first log house in the fall of 1859. William W. Raymond moved one from Slaterville to Plain City in the same year. John Carver’s log house was built in the fall of 1860. Thew log came from North Ogden Canyon. This log house has been moved on to the grounds behind the LDS Chapel and is being taken care of by the Daughters of the Utah Pioneers of Plain City.

The logs in both the Skeen and Carver homes came from the North Canyon after a road there had been partially constructed by Plain City men. This road was finished in1860 and became a toll road.

The preparing of logs for building was a tedious process. They were hand sawed in pits dug for his purpose and were trimmed with axes. The first shingles were hand made. Saw, chisels, and hammers were used in their construction.

William Skeen’s log house was one of the early log homes of Plain City. It’s still standing on the lot one block west of the school house. A little later William Skeen added an adobe section to this house. In1862 or 1863, he built a stone house of rock hauled from the hot springs northeast of Plain City. William Sharp, an early Plain City brick mason, laid the stones and assisted Thomas Singleton, and early carpenter. Gunder Anderson built the first adobe house in Plain City two blocks north and one block east from the northeast corner of public square.

Statement of Lorenzo Lund: “I stood on this street one 17th of March (the one running north and south on the west side of the public square.) and heard Lyman Skeen and Gus Petersen talking about the old adobe house on the Berry lot. Mr. Peterson said that he assisted his father in the construction of that house when he was nine years old.” David Booth lived in this house and was a manufacturer of hats. He made these hats from rabbit skins.

The first nails used in Plain City were in the adobe house of Gunder Anderson and made by Christopher O. Folkman. He hammered them out in his blacksmith shop. They were square nails.

“Alonzo Knight moved his log house in union on little cottonwood southeast of Salt Lake in the fall of 1859, after his crops were in. It consisted of two log rooms with a court between, roofed over, and an adobe wall at the back, the front of the court being open. An adobe fireplace in the center, while a large oak swill barrel stood on the side opposite to the granary which was stored in separate compartments in the granary. The fireplace in the center was used for baking in the summer. On the west side of the house was a milk cellar which was connected with the west room by a door. Our bread, mostly corn, was baked in a bake kettle in the fireplace. Cornmeal was also used in making mush. The husking of the corn took place in the winter. Each log room had two windows; one in the front and one in the back. An 8×10 inch glass was used. The beds were home made. My father had the first big orchard in Plain City. He had apples, peaches, green gages, sand cherries and squash. The boys came and from all over Plain City for William to roast squash in the big bake oven for them. An Indian, Captain Jack, wanted my mother to give me to him because I had red hair.” Amanda Knight Richardson.

Interior of Christine Swensen Miller’s dugout home as described by her sister Josephine Ipson Rawson.

“This home stood on the lot that Milo Sharp afterward bought. There was a door in the east end with a small window by the side of it. It was very dark in there when the door was shut. Just inside the door to one side was the flour barrel. The bed was in the northwest corner. It was homemade and consisted of four posts held together with boards fastened to the ends and sides. There were knobs fastened to the side and end boards for holding the ropes that were stretched across to form a sort of mesh rope springs. The ticks were filled with oat straw or corn husks which had been torn into fine strips with forks. The homemade furniture was made from very light white wood.

The food was mostly potatoes fried in an open skillet over the fireplace. Sometimes a wild sage leaf would get into them nearly ruin them. Sacks were stuffed in the chimney when there was no fire to keep out the cold. Sometimes the fire was lighted before the sacks were taken out and nearly set the house on fire.”

Among those who built adobe houses were John England, Gunder Anderson, George Musgrave, William Raymond, Hans C. Hanson, Peter C. Green, Charles Neal. (Incidentally, Mr. Neal and his wife Annie England Neal dragged willows from the Weber River, 2 ½ miles away, in order to build a fence around their lot.)

Callie Stoker’s house is the oldest occupied house in Plain City today.

George Musgrave’s first one-room adobe house replaced his “dugout” on his first lot two blocks north from the square. He next moved one block east. Here, he erected a two or three-room house, containing one large room on the west where he conducted his school and dancing parties.

Mrs. Mary Ann Winfield Spiers held her girls school of sewing. She also held classes in reading, writing, arithmetic, spelling, and fancy work. She made the first crochet hook out of the heart of sage brush. She wittled it down and then smoothed it with a piece of broken glass. This is what she taught the girls to crochet with. The next was a crochet hook made out of a broken knitting needle. She taught in a log room on their lot located one block south of the public square.

Interior of William England’s “dugout” about 1862, described by himself.

“Our dugout” was located just west of where William Hunt’s home now stands. The inside was adobe lined, and adobe fireplace stood on one side with its pile of sagebrush nearby. The soil then in Plain City was quite dry so that it was very comfortable inside. The floor was of hard-packed dirt. Hard enough to scrub. It had a dirt roof – a door in one gable end and a window in the other end.

Our furniture was all homemade, of slabs and willows. There was a cupboard built in one side for our dishes, which were brought from England. Large willows were used in the construction of the bedstead which was lashed with bed-cord. Our ticks were filled with dry grass and rushed from the nearby slough. Annie was born here. Our provisions for the first year consisted, (in the main) of 5 gallons of molasses, 5 bushels of potatoes, 5 bushels of wheat, and other miscellaneous food items which we obtained by labor and purchased. We lived here for two years, them later, we bought out a Scandinavian by the name of Larson and built a one-room adobe 12×14 with a dirt roof and dirt floor, with one window and a door made of rough lumber. We lived here eight or ten years, then moved out east on our farm,” William England.

The frame work of the chairs was usually made of cottonwood or willows with rawhide or cane seats.

In the house where Josephine Davis Ipsen was born, her mother, Anna Beckstrom Davis, slept on the wheat in the wheat bin and here is where Josephine was born.

Lumber and glass began to be used in the construction of homes in Plain City in the early sixties. Some furniture was made of dry good boxes. Tree stumps were sometimes used for chairs. The first dishes were carved from wood. Some crockery was obtained from Brown’s Crockery Factory at Brigham City.

Cottonwood and willows from Weber River were used quite extensively in the construction of the early homes. Later lumber was obtained from Wilson’s saw mill in Ogden Canyon. This was hauled down by ox teams. Three or four days were required to make the trip.

Household furnishing of John Moyes’ home as given by his daughter Sarah Moyes Gale.

“The benches, tables, and cupboards were all homemade. There were no nails to fasten the boards together so wooden pegs were used. About 1967, we got some store furniture, a lounge and a bed which was used as a pattern for other furniture. Slabs and rough boards were used in making our homemade furniture. We usually whitewashed our adobe with whitewash which we made from the clay at “Cold Springs.”

Our first broom were made from sagebrush, rabbit brush, then later, from broom corn.

We painted pictures with paint from colored cloth soaked in water.

Our first stove was a little “step stove brought across the plains.” It cost $100. Father bought a sewing machine at the same time.

There were no screens for doors or windows. We made fly catchers of straw tied together with string and made in a rosette. Curtains for our dry-goods boxes furniture were made of calico obtained from Salt Lake City. Our tubs, spoons, bowls, etc., were of wood. Also, our churn and spinning wheel (except the head and spindle.)

Our fuel was mostly sagebrush, willow etc. I remember when Christopher O. Folkman brought a piece of coal to school to show the children.

Our first lights “bitch lights” were made of trips of cloth twisted together and set in a dish of grease. Then came tallow candles made in a wooden mold. Our mold went all over the town. Everyone took tallow candles to the meeting house for a party or dance. Sarah Gale and Lyman Skeen.

EARLY TREES

John Hodson planted many tees both shade and fruit trees around his home. He also planted the large tree that grows by Elmo Read’s place. Joseph Skeen planted many trees also. Those who planted fruit trees earliest in Plain City were: John Spiers, Alonzo Knight, William England, Charles Weatherston, Hans Lund, Peter C. Green, Otto Swenson, Abraham Maw, James Rowe, John Carver, William Geddes, Edwin Dix, Jonathan Moyes, Fred Rolf. John Carver planted two rows of cottonwood trees by his place. The favorite fruit trees were: apple, peach, cherry, pear, plum. The favorite shade trees were: poplar, cottonwood, boxelder, locust, mulberry, catalpha, basewood, black walnut. The mulberry trees were a reminder of the attempt to establish a silk factory in Plain City.

SMALLPOX

Meetings were discontinued in Plain City from September 30, 1870, to March 5, 1871 on account of a smallpox epidemic which was raging in the community. On the 1st of November, 1870, a meeting was held relative to preparing a place near Salt Creek for the smallpox patients. (Ward minutes.) This place was built, but found to be small, so on the 2nd or 3rd of November it was enlarged. It was not a success, however, as the facilities for caring for the patients were poor and meager. The house was cold and drafty, which caused the death of many who would have survived with better care.

Some families suffered a severe loss, among these were William Skeen, Alonza Knight, William Gampton, and many others; nearly every family suffered some loss.

WEAVERS

The first weavers were Mary and Trina Hanson. John England wove cloth, his father being a weaver in England and perfected the first, if not the very first power loom used in this country.

Mary Katherine Shurtliff operated a little store in connection with her weaving. Anna Beckstrom Christensen could shear a sheep, spin the wool, and weave it into cloth. Catherine Folkman and Susannah Richardson also wove carpets.

SILK INDUSTRY

Erastus Snow in early days advised the pioneers to plant mulberry trees and raised silk worms. Several trees were planted (many of which are still standing today) and the worms obtained, but the industry was soon abandoned as it was not profitable. Those who planted trees were: the Geddes family, Jeppe G. Folkman, Bertha Lund, Anna Christensen, Mr. and Mrs. Lindilof, Elizabeth Moyes. Elizabeth Moyes was engaged in the manufacturing of the silk.

SHOE MAKERS

Thomas Wilds and Millie Himston’s grandfather.

CARPENTERS

Hans Petersen, who built his own adobe house, Thomas Singleton and his brother Charles. William Sharp was also a plaster, stone mason and adobe maker.

Joshua Messurvy, who superintended the building of the meeting house benches, built the pulpit in the meeting house. A beautiful work of art, being all inlaid work, made from wood of different kinds of trees was done by William Miller.

MIDWIVES

Annie Katherine Hedwig Rasmussen Hansen, wife of Hans Christian Hansen, was the first midwife in Plain City. She came here between 1860 and 1862, while her husband was on a mission to Denmark. She was born in Forborg, Denmark, October3, 1823. She was baptized January, 1852, came to Salt Lake City October 1, 1853, moved to Ogden, later settling first at Bingham Fort, then in Harrisville. She was asked by the bishop of Plain City to come down and practice her profession. Her log house at Harrisville was torn down by the men the bishop sent, carried to Plain City, and re-erected on a 2 ½ piece of ground, which the ward gave her. Sister Hansen was among those called to take a course in nursing and obstetrics, under the direction of Eliza R. Snow. She practiced in Plain City for many years. She died March 31, 1899.

Jane Pavard England, wife of John England, was another early midwife, coming in 1862. She was set apart for this work on the ship while coming over and promised that she would be very successful. This promise was literally fulfilled. She was born August 2, 1815, near Yeoble Somerset, England. She died in Plain City on November 20, 1882.

Another midwife was Elizabeth Murray Moyes, daughter of John Murray and Sarah Bates, and wife of John Moyes. She was born December 24, 1840, at Elizabeth-town, Michigan. She came to Sugarhouse Ward in Salt Lake in the early ‘50’s. She and her husband moved to Plain City in October, 1865. She learned obstetrics from Dr. Shipp in Salt Lake City. She practiced in Harrisville, Warren, Farr West, Plain City for twenty years. She died on January 4, 1905, in Plain City of pneumonia.

Martha Stewart Geddes was another midwife. She was born May 10, 1838, in Scotland and died August 11, 1900 at Plain City.

IMMIGRATION FUND

A company was organized at the October conference of 1849, for the purpose of facilitating the gathering of the Saints of Zion. It was incorporated and a committee appointed to gather funds to be used in assisting the saints of foreign countries to emigrate to Zion. It continued until 1887, when it was discontinued through the passage of the Edmund Tucker Act. Its funds were confiscated by the U. S. Government and distributed among the schools. It was a perpetual self-sustaining fund because those who received aid were supposed to return to the fund the amount they had received, as soon as they were able. The sum of the original cost contributions was $5,000. There was $2,000 in gold raised by the British Saints.

The pioneers were called upon donations of the time, oxen, wagons, and money. As many as 500 wagons were furnished some seasons. Plain City assisted in this as they have always done in every worthy cause. On May 25, 1873, donations for the immigration funds was received from those faithful pioneers of Plain City.

On May 22, 1874, a meeting for the considering of the Organization of the United Order was held. Committee members were: L.W. Shurtliff, President, John Carver, assistant, John Spiers, Secretary, George W. Bramwell, Assistant Secretary, Jens Peter Folkman, Alonzo Knight, Peter C. Green, managers. On August 15, 1875 the rules of the order were read. (From Ward records.)

ECCLESIASTICAL HISTORY

Plain City Branch was organized in May, 1859, by President Lorin Farr and Bishop Chauncy W. West. William Wallace Raymond was appointed president president of the branch with Danial Collett and Jeppe G. Folkman, counselors, and John Spiers as clerk.

Danial Collett moved to Cache Valley that same year, so John Carver was called to fill the vacancy.

At this meeting the settlement received its name of “Plain City,” Someone had suggested City of the Plains, “but this was rejected as being too long, so the name of Plain City was chosen. This little settlement was a town on the plains away from any one town. It was a city of the plains.

REMINISCENCES OF MARY ANN CARVER GEDDES

“I remember a meeting held in the adobe meeting house. Eliza R. Snow and Jane R. Richards were in attendance. We knelt on the dirt floor. Sister Snow said we little girls would live to see the day when time would be “hurried.” Our light came from fine pieces of sagebrush piled on the hearth. We had one corner where we kept the big pieces for heat and another where we kept the small pieces for light. In 1861, a country precinct was organized at Plain City with Abraham Brown, Justice of the Peace, and William Geddes as constable. A post office was established in 1864, with William W. McGuire as the first postmaster. He brought the mail in his high silk hat to church and distributed it among the congregation. At this time it required 2 ½ days by ox team and 2 days with horses to go to Salt Lake City and back.”

Joseph Skeen was appointed water master with Ezekial Hopkins and Jeppe G. Folkman, assistants. Mr. Folkman remained in his position until May 2, 1872.

On May 22, 1870, President Raymond resigned his position as President of the Plain City Branch.

On August 21, 1870, Lewis W. Shurtliff was appointed President, with John Carver as 1st Counselor, and Jeppe G. Folkman and 2nd Counselor. William W. McGuire was presiding teacher.

At the Weber Stake Conference, held on May 27, 1877, Lewis W. Shurtliff was appointed Bishop of the Plain City Ward. He was sustained by the people next day, May 28, with John Spiers as 1st Counselor, and Peter C. Green as 2nd Counselor. Franklin D. Richards, John Taylor, Erastus Snow, and D. H. Perry, officiating.

On December 15, 1878, a cemetary committee was appointed. It consisted of: Charles Neal, Charles Weatherstone, William Geddes, Jens Peter Folkman. On January 22, 1883, George W. Bramwell was appointed bishop.

On May 3,1883, some means were collected to build a poor house.

REMINISCENCES OF WILLIAM ENGLAND

“The settlement became prosperous and it wasn’t long before Plain City became known far and near for its delicious fruits and vegetables.

Fifty-nine years of my life have been spent here. When I settled in Plain City in 1862, there were a few one-room adobe houses and one or two log houses. The main part of the town was laid out. The north lane and the Poplar district was added later. Charles Weatherstone’s was the farthest street south. Higbe lived on the Weber River and ran a ferry boat. The first ferry boat was molasses boiler. This was then the main road to Salt Lake. I never met any hostile Indians on the “plains.” I want to relate an incident, a man carried away a relic from an Indian burial ground. The captain of the company made him go back and return it. He was gone nearly all night.

My first job in Salt Lake was stripping sugar cane for john Young. I received one gallon of molasses for her days wage, two quarters of which I ate for super and the rest in the morning. I never had any extreme hardship. Our parties lasted nearly all night. We danced by the light of tallow candles and sagebrush fire. A lunch was served at midnight.”

Lyman said that when his father, Joseph Skeen, first came to Plain City, he brought a tent with him and that is where some of the first meetings were held.

SCHOOL HOUSE AND MEETING HOUSES

The first school and meeting house was built in 1859. It was of adobe 18 x 24 feet and was located of the south side of the public square, just opposite and a little northeast of the present meeting house.

It faced the east. It had a dirt floor and roof. There was a door in the east end, a fireplace in the west and two windows in each side. Men were called to make adobes for a meeting house, school house, and amusement hall for a number of years. The furniture hung on the two sides to be used as desks, one for the boys and one for the girls. These were dropped down while a dance was in progress. We had no textbooks. In McGuire’s school we had square pieces of boards with the letters of the alphabet burned in them, which we were supposed to memorized.

Oral spelling was the rule. George Musgrave was the first school teacher. His first school was held in his “dugout.” Mary Ann Geddes

George Musgrave was also a musician and gave private lessons. He also was the first choir leader. In 1863, a split log addition to the meeting was built on the east end. It was 12x 18 feet. At this time, the whole building was shingled from shingled brought from Salt Lake City. A bowery of willows was constructed near the meeting house to be used in the summer time.

In 1863, when the addition was built, the meeting house was plastered for the first time. A rough table was placed in the west end to be used as a pulpit. Sagebrush for the meeting house was hauled from the north range and Little Mountain.

On April 16, 1871, a vote was taken in Sunday meeting concerning the building of a new meeting house. A committee was appointed on June 25, 1871, to oversee the building of the new meeting house. President L.W. Shurtliff, John Spiers and N.P Lindilof were appointed. They decided to build it to adobe. On July 9, $15.00 was collected to begin building on July 8, 1879, W.W McGuire Secretary, and Charles Neal, Treasurer were added to the committee. On September 18, 1870, W. W. Raymond, William Geddes, and William VanDyke were appointed to act as school trustees. This new meeting and school house was completed in 1873 or 1874. It was in use as an amusement hall as late as 1907. It had a small stage in the north end and a small entrance room on the south.

On May 5, 1874, the ward minutes state that the first meeting was held in the new meeting house. The organ is mentioned for the first time.

William McGuire was the second school teacher. The first one to teach in the little adobe school house on the south side of the square, as I can remember. Mary Ann Geddes.

William Geddes carried part of the bible to school to learn to read from it. We also read from the church publications, Harpers Weekly, The Contributor, Women’s Exponent, etc. the first reader I remember were Wilson’s, Bancrofts, Meguffeys. We studied grammar from Pineo’s’ Primary Grammar. Arithmetic from Rays Arithmetic. In McGuire’s school we also had a blackboard with the letters of the alphabet on it. Some of the literature we read was, Ogden junction, Millennial Star, Journal of Discourses, bible, Doctrine and Covenants, Book of Mormon. I attended school in 1873 at George Musgrave’s home. Mary Geddes.

There were no school bells in those days. The master, Mr. McGuire, called the school together by going to the door and shouting, “Books, books,” at the top of his voice. The pupils ran as fast as they could for woe be to the laggards. If a child misbehaved and was not caught, the whole school was “thrashed” in order to punish the guilty one.

He bible was the principle textbook used. Those who could afford slates had them. The first slate I ever had was a piece given to me by Seretta Raymond. It had broken off from her slate. She gave me a little piece to use as a pencil. In order to keep Jack Spiers put of mischief, Mr. McGuire tied him to the table leg. George Spiers said, “Minnie Carver would be the best girl in school if the rest didn’t spoil her.” M. A. Geddes

All these first schools were tuition schools. A tuition of $3.00 per quarter was paid to the teacher by the parents who were also required to furnish all necessary supplies to their children.

EARLY AMUSEMENTS

The people have always fostered amusements and entertainment of various kinds. The various show companies who have staged plays there have referred to it frequently as a “good show town.” This is probably due to the fact that several among the early pioneers were gifted with dramatic ability and fostered and encouraged the art in the little new community.

Plain City, like all Mormon settlements has also encouraged dancing as a form of recreation. The very first year of settlement, before they had time even to construct a suitable place, they held a dance. It was on the 24th of July, 1859. The place was the “Barrens” down west of the settlement. The music was furnished by a “comb band” and many of the dancers were barefoot. Everyone had a good time regardless of the conditions under which they were dancing.

“Numerous parties were held at the private homes. They danced outside on the dooryard which was hard as rock.” Susannah Robinson Beddes

“Once when Thomas Carliss came from Kay’s Ward to visit the Eames’, The Wadman’s, and Carver’s, he brought his fiddle along and we put on a dance.

The young folks danced frequently on the public square. Mrs. John Spiers wore the first party dress I ever saw.

On of the ways of entertaining ourselves was to gather around some neighbors hearth and sing songs. We liked to meet Hansen’s because they were all such good singers. David Booth and his brother, Henry, sang “Larboard Watch” very beautifully together. Abraham Maw and his wife, Eliza, sang duets. We usually dropped in at some neighbors to spend the evening. After the molasses milks were built, we young people had frequent “candy pulls.” They gave us the “skimming” to make molasses candy.

We also had “cutting and fruit drying,” corn husking, wool picking, rag, hay picking, and quilting bees. After the work was cleared away, we would sit in a circle and play games such as pass the button. Our refreshments were usually molasses cake, dried apple pie. The apple were cut in 4 pieces and laid upon a roof to dry.

We had frequent picnic parties. At our dances in George Musgrave’s school house, John Moyes often played his accordion. We liked to play “Run Sheep Run” and “Hide and Seek” down in the west end of town. Charles Singleton and Eliza Ann Turner Singleton, his wife, enjoyed this sport with the rest of us “kids.”

There were bonfires at the end of each goal. George Draney was the fastest runner in Plain City. (Mary A. Geddes)

In the winter there were bob sleigh riding parties. The horses had sleigh bells on their harnesses which jingled as they ran.

Our dances in the winter time commenced in the afternoon and lasted well into the evening. Dances were held in the old adobe school house on the south side of the square in the winter and in the bowery which was nearby in the summertime.

We danced on the hard dirt floor at first, many in their barefeet. Some had fancy boots on. My brother, Mathias Lund, had purchased a pair to wear at a dance in the old bowery and being a “fussy” man, had gotten them plenty snug. When he tried to get them on he couldn’t, so he removed his socks, greased his feet, and they slipped on without any effort. He went to the dance and danced the finger polka and the mazurka with the best of them. (Willard Lund)

During the holidays, parties were held at Charles Neal’s, Folkman’s, Spiers’, Shoemaker’s, Gaddes, Eames’, Carver’s and other homes in Plain City.

The choir usually gave concerts during the holidays. On Christmas eve, they usually serenaded the town and the band serenaded on Christmas morning.

I remember once when mother was baking custard pies for a party in the big bake oven. Some of it got tipped over and was discarded as not fit for “company.”

So, we children had our fill of custard pies for once. (M. A. Geddes)

Church fairs were held in the school house. Booths of various kinds were arranged around the room, also “fun houses”, auctions, etc. The band was always in attendance. Much of the money for the financing of the church building was obtained through theses church fairs. Once, Becky Hiatt, Rill and Zell Smith wished to attend the fair at Plain City, so Becky and Rill made three dresses in one day. Then Becky fried the chicken for lunch and Zell made the cake and they came to the fair and danced. (Rebecca Hiatt Weatherstone)

In the fall of 1868, Mrs. Musgrave’s daughter, Louisa, rode horseback from Plain City to Ogden to take charge of the fancy work booth at the fair. The first amusement hall erected in Plain City was a frame building that stood one block south, from the southeast corner of the public square. It was erected in 1890 at a cost of $2,500. This amusement hall served the people for about 13 years when it was accidentally burned. Besides this hall there was the Berryessa hall located one block south corner of the square. After the destruction of the ward amusement hall in 1930, the people once more used the old adobe house on the northeast corner of the public square as a recreation center. In 1913-1914, a brick amusement hall was erected south of and adjoining the meeting house. It had classrooms below. It had hardwood floors, a stage, and equipment. On the committee was Lynn Skeen, John Maw, and Stephen Knight.

On Christmas, we usually had a program in the morning and a childrens dance in the afternoon. The Sunday School always had a Christmas tree with presents on it for the children. Everyone brought candles to the dance for light, until coal oil lamps began to be used. Our first coal oil lamp was one that fastened on the walls with tin reflectors at the back. Then came fancy chandeliers that were fastened to the ceiling, also various kinds of table lamps. Then the gas mantle lamps and finally electricity came.

We told them the time of day by means of a contrivance that followed the shadow of the sun around. Consequently, we couldn’t tell the time on a cloudy day.

MUSIC AND DRAMA

Plain city in early days always had a brass band, a choir, a dramatic association and a baseball team. The first band was organized in 1864 or 1865 with Thomas Singleton as leader.

A man by the name of George Parkman came up from Salt Lake City to organize the band and give lessons to the players.

The first instrument were purchased from Fort Douglas band. The money being raised by donations of cash and molasses.

Will Geddes gave the first $5 and others soon followed his lead. The organization took place in front of the old Singleton home.

Some of the members are recalled by Mr. Singleton as: Charles Neal, William Stewart, Charles Singleton, William Sharp, Abraham Maw, Edward Goddard, Lorenzo Thomas Musgrave, and William Geddes.

The second band was the Heath band. The instruments for this band were obtained in the east. The money was raised by the Dramatic Company of Plain City.

Charles Heath was the leader of this band. He did all the early painting in Plain City. He painted the scenery for the dramatic association and was president of the association for some time. Some of the members of his band were Alfred Bramwell, John Bramwell, Frank Bramwell, Abraham Maw, William Geddes, William Stewart, Haskell Shurtliff, Richard Lund, James Lund, Henry Eames, Robert Eames, Joseph Geddes, Samual Draney, and Thomas Cottle.

The first dramatic association consisted of Louisa Hopkins Moyes, Edwin Dix, Charles Heath, O. J. Swensen, David Booth, Victorine Musgrave, Mary Ann Sharp, Elizabeth Sharp. Some of the plays were: “Ten Knight in a Bar Room,” “Emmeraldo or Justice of Takon.” “Charcoal Burner,” and many other good plays. The traveled around to the different towns.

The second dramatic association consisted of:

Joseph Geddes, Joseph Skeen, Henry Eames, Mary Ann Carver Geddes, Elizabeth Eames, Lillie Stoker Sharp, Annie Hansen, Samual Draney, Josephine Ipson Rawson, Charles Heath, As leader, Archabold Geddes, Alfred Bramwell, Frank Bramwell. They presented the following plays: “Mistletoe Bough,” “Mickle Earl” or “Maniac Lover,” “Fruits of the Wine Cup,” “Streets of New York,” “The Two Galley Slaves,”: The Rough Diamond,” “ Earnest mall Travers,” “ Ten Knights in a Bar Room.”

Sara Singleton was the little girl who sang the song “Father, O Father, Come Home To Me Now.” This company played in Willard, Harrisville, and other surrounding towns. They raised $400 to buy band instruments for the Charles Heath Band.

SPORTS

Plain City always prided itself upon having a good ball team. At one time their baseball team conquered all teams they played except Salt Lake. During this period their greatest rival was the Willard Team, which possessed a curve pitcher. This was something new in baseball at the time. Earnest Bramwell of Plain City learned from Mr. Wells how to throw a curve ball and became the second curve pitcher in Utah. Members of the baseball team included: Catcher, Willard Neal, Catcher, Hans P. Petersen, Catcher, Levi Richardson, Pitcher, Joseph Geddes, First base, Milo Sharp, Second base, Cornelius Richardson, Third base, Willard Neal, Right field, Madison Thomas, Center Field, Fred Wheeler, Left field, and William L. Stewart as short stop.

INDUSTRIES

Every pioneer family had its lye barrel for extracting lye from wood ashes.

Around perforated of wood was fitted inside the barrel near the bottom, upon which greasewood ashes were placed. Water was poured over these ashes and it settled in the bottom of the barrel carrying the lye from the ashes in the solution. This was combined with grease and boiled down to soap. When it was “done” it was poured into a tub to cool and harden. Then it was cut into squares and placed upon a board or table outside to dry.

Salt was extracted from the water of the Great Salt Lake. Soda was made from Alkali.

Fine Starch was made from potatoes grated fine and the juice pressed out and placed in the sun to dry.

Flour starch was used to starch common things.

Wool was spun into thread and then woven into cloth. The wool which was gathered from the fences and bushes was washed, carded, and made into bats for quilts.

Some nails and bullets were made in the home. Also, rag carpets and rugs were home manufactured.

Candle dipping, spinning, weaving, hand sewing, knitting, crocheting, tatting, were done at home. When a pioneer lady wanted a piece of lace or embroidery for herself for a petticoat or a dress, she made it herself or engaged her neighbor to make it for her.

Then there were the quilting of quilts and petticoats, hat making, broom making, etc. In fact, most of the articles in daily use in the home were made by some member of the family.

STRAWHATS

Straws were split, soaked, braided either in three or four, five or seven-strands lengths, sewed together along the edges to make the hat. This was then rolled, blocked, and pressed. Minnie Hansen Lund taught hat making in Plain City. Josephine Ipson was one of her pupils.

Susannah Robinson learned the art of making straw hats from Annie Dye, wife of Joseph A. Taylor.

David Booth made beaver hats from rabbit fur.

FOOD

Sweetening was made form the juice of sugar cane and watermelons. The juice was pressed out and boiled down to a syrup. Fruits and vegetables were dried. Everyone made their own butter and cheese and raised their own vegetables and fruits.

Vinegar was made by getting the vinegar plant, called the “Mother” pouring water over it and adding sugar or some sweetening and letting it stands in a warm place until the proper state of acidity was reached. Some vinegar was made from apple juice.

Shortbread was eaten at first. Then with the introduction of white flour came “salt rising bread,” also “sour dough bread.” Corn bread was used a great deal also.

After the yeast germ was introduced, people began using more bread leavened with yeast. They would save a little start of this yeast from one mixing of bread to the next and add potatoes, water, and sugar.

In every community, there were women who specialized in making yeast, which they exchanged with their neighbors for flour. Annie Neal did this.

Meats were pickled in brine or dry salted for summer use. It was also smoked in the cold winter and kept frozen. Relief Society as told by Mary Ann Carver Geddes.

A Relief Society was organized in Plain City on January 3, 1868, with Almira Raymond as President, Margaret Shoemaker as First Counselor, Mary Ann Carver as Second Counselor, Victorine Musgrave as Secretary, Succeeded by Mary Ann Spiers and Annie Folkman as Treasurer. Mrs. Alice Robinson and her partner Anna Eames walked to Warren, a distance of four miles through deep sand to visit the families who lived down there and give them aid if needed.

Most of the donations in those days were in produce.

Many of the meetings were devoted entirely to work and business. The sisters brought their spinning wheels and spun yarn for the society. Even the children helped.

One of the duties of the relief society teachers was to gather up donations of soap, clothing, or anything the people could give, which was distributed among those in need. They also sat up nights with the sick, gave them food, clothing, or whatever was needed.

THE WHEAT PROJECT

Eliza R. Snow came to Plain City to start the storing of wheat. Those who didn’t raise wheat of their own went into the fields to glean. The work was all done by hand. The wheat was cut with a cradle, raked with wooden rakes, and piled in small piles.

SALT

The salt industry at one time was quite a thriving industry and employed many people. It helped very materially in the financing of the ward.

The salt pits were located northwest of the town on the edge of the Salt Lake. At one time, there were as many as twenty camps with 100 people on the payroll. Many girls and women from the surrounding settlement helped gather the salt and also cooked for the men employees. The coarse or unrefined salt was obtained by digging pits, filling them full of salt water in the pits. The crude salt was hauled by teams to the Hot Springs and shipped to the mining towns of Montana to be used in the smelters and also on the cattle ranches. It was also hauled to Cache Valley and traded for grain. Some finer grains of salt were refined by boiling the salt water in woodlined vats called salt boilers and over sagebrush fires.

Those engaged in the salt business were Clayborne Thomas, Jens Peter Folkman, Charles Neal, William Geddes, Joseph Geddes, Christen Olsen, And William Steward. They contracted to deliver salt to the smelting companies of Montana and worked up a lively trade.

Some of those who worked at the “salt works” were Caroline Palmer, Ellen Peterson, Frances Carver, Martina Peterson, Matilda Folkman, Sarah Moyes, Nephi Hansen, and Jens Peter Folkman and a salt mill at the latter’s home where the salt was ground and sacked ready for the market. Matilda Folkman, Sarah Moyes, Cordelia Moyes Carver, sewed the sacks.

BRICK YARDS

A suitable clay was found on the banks of the Weber River for the making of brick.

Joseph Geddes clay was found on the banks of the Weber River for the making of bricks.

BUTCHERS

The early pioneers raised their own meats. They raised and slaughtered their own beef and hogs and sold the meat to the people from their “meat wagons” which made regular runs through the town. They also made stops in the nearby towns. John England owned the first slaughter house. It was located 1 ½ miles northeast from the public square of the Hot Springs road. Jens Peter Folkman and John Vause had the first butcher shop.

Gus Peterson had a “slaughter house” and a “meat wagon.” He ran his business on a sort of co-operative plan. People put in their beef and pork and drew the value out in fresh meats as they wanted it.

Jens Peter Folkman ran a “co-op” butcher shop. Also, Peter M., his son, had a butcher shop.

Maroni Skeen and Fred Rolph did the killing for a large firm of butchers.

FRENCH RETRENCHMENT SOCIETY