Interview of Milo Ross

By

Wayne Carver

08-13-1997

Tape I – A

University of Utah Veterans Commemoration in 2009

Wayne: Okay. I’m at Milo Ross’ home in Plain City, which is just through the lots from where I grew up at and the date is what, August the 13th?

Milo: Probably the 13th today.

Wayne: Wednesday August 13th. This is tape one, side one of a conversation I’m having with Milo.

(tape stopped)

Milo: Should have put on there Plain City.

Wayne: Oh, well, I’ll remember that. But I have trouble if I don’t do that little preliminary stuff, is I get the tapes mixed up. You have a quiet voice, so I think I could find a book or something to – oh—

Milo: Here’s one right here.

Wayne: Just to prop this –

Milo: How about this? What do you need?

Wayne: Just something like this.

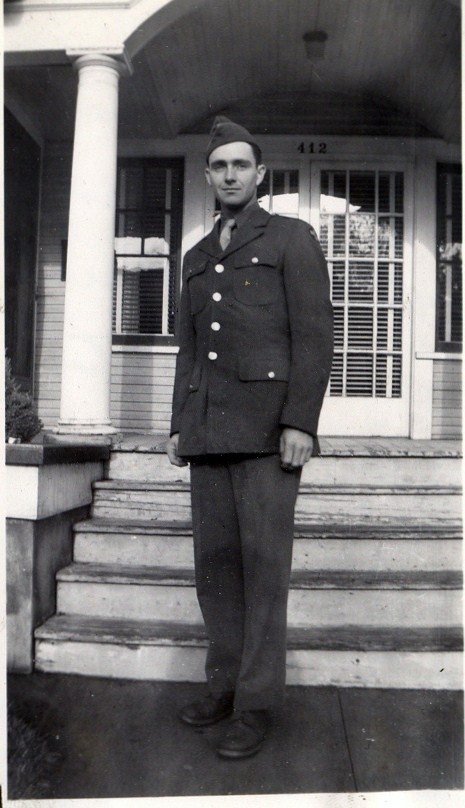

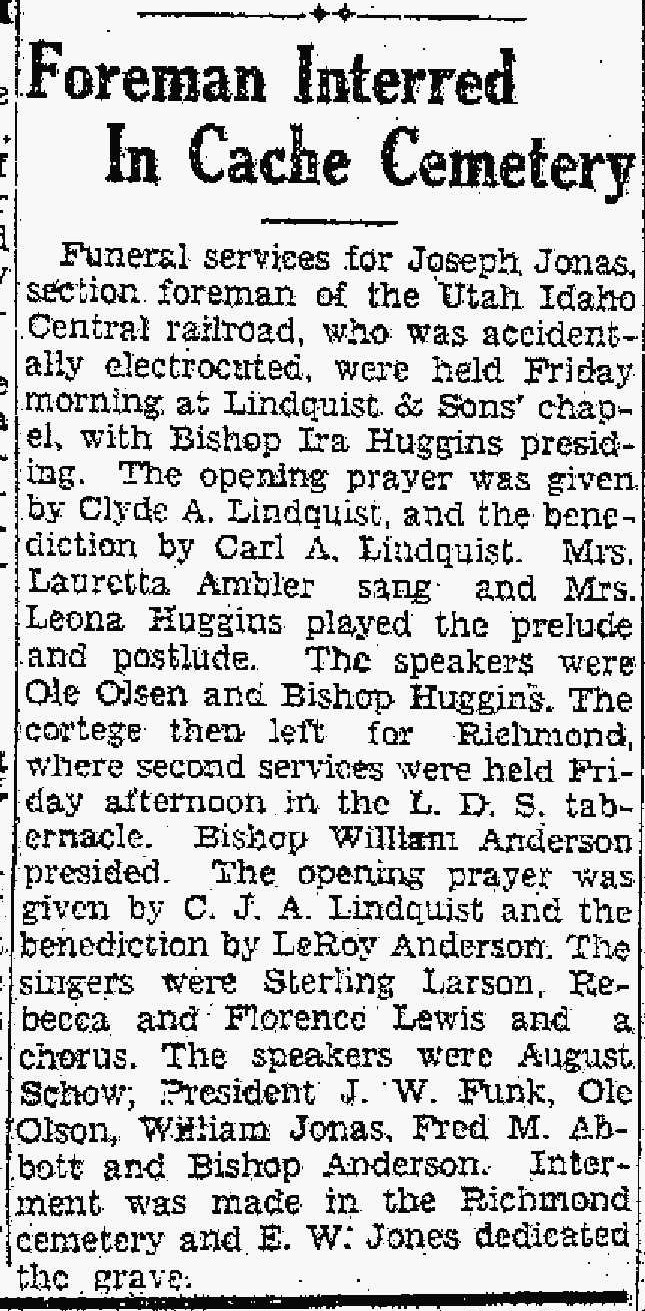

Milo Ross in uniform at Fort Lewis, Washington

Milo: Oh

Wayne: Since I want –

Milo: Here’s some more book. You know, you said you was talking to Aunt Vic Hunt. I’ll tell you a story about her. She’s over to the rest home, see. Yardley, he came in and he says – he and an attorney came in and he says, Mrs. Hunt, he says, you sure got a rhythm out of heart. He says, you gotta start moving around taking it a little more easy, don’t hurt yourself. She says, “listen you young punk.” she says, “Why don’t you tell me something I don’t know anything about. I’ve lived with that all my life,” she says.

Wayne: Well Paul – or Milo, can I just ask you a few obvious questions for the — and then – can you tell me your full legal name?

Milo: Do you wanna start now?

Wayne: yeah.

Milo: My name’s Milo James Ross.

Wayne: And what date were you born?

Milo: February the 4th, 1921.

Wayne: So, you’re two years older than I.

Milo: Born in ’21.

Wayne: Right, I was born in ’23?

Milo: ’23.

Wayne: Yeah. Where were you born?

Milo: Plain City.

Wayne: And who were your parents?

Milo: My mother was Ethel Sharp Ross. That’d be Vic Hunt’s sister. Ed Sharp’s sister, Dale Sharp’s sister. My dad was Jack Ross. And he came from Virginia. They came out west and settled over in Rupert and Paul, Idaho. When they found out they was gonna have a sugar factory in that area. So, they run the railroad track a ride out. What they really done, they bummed their way out on the railroad, flat cars at that time. They was bringing coal and stuff out from Virginia out into that country. And Dad and Grandad and all the relatives that could decided to come out. And that was the only way they could afford to come out because nobody had any money. So they settled around Paul and Rupert, Idaho area. And that’s where my dad met my mother, Ethel Ross, because she had that store I was telling you about in Paul.

Wayne: Yes, go back and tell me again for the tape how your mom got up in Paul running a store.

Milo: Well, the – when they were going to work and back and forth from Plain City in to Ogden, they used to ride the Old Bamberger track out here. And when they – when the first came out, they had a – it was an electrical trolley car, you probably remember it had an arm on top that had –

Wayne: Right, yeah.

Milo: — Track. I remember riding the car once and I was down to Wilmer Maw’s helping them unload coal and stuff like that out of the boxcars down there. But that old dummy car used to bring them cars down there. They had a spur at Wilmer Maw’s store and also at Roll’s garage. Stopped right there.

Wayne: That’s right, yeah, I remember that.

Milo: Then they used to ship vegetables and stuff out from the railroad track from there out. But mother was going to Ogden on this – I don’t know how – how you call it a Bamberger Track Car, Trolley Car, or whatever you call it. But when they got making a turn and transferring, probably around 17th street in there where they used to be the headquarters, they got bumped and some of them got knocked down and hurt. I never did find out how bad my mother was, but the railroad company settled out of court and give them all so much money apiece, the ones that got hurt.

Well, my mother, she knew of a place in Paul Idaho that had some property. She decided to go there and buy that little store front and live in Paul, Idaho, because she married this Mark Streeter at that time. Maybe you remember him.

Wayne: oh, yes, yeah.

Milo: Mark Streeter. They went into Paul, Idaho and –

Wayne: Was she married to Mark?

Milo: She got married to him –

Wayne: When the accident occurred:

Milo: No. not – not – just after.

Wayne: uh-hu.

Milo: But she got the settlement and he found out that she had the money and everything and she had gone to Idaho, so I figured he – he probably figured she was a rich old dog, he went to Idaho to marry her.

Wayne: I see yeah.

Milo: So he went to the – up the store, Paul, Idaho, up there and they got married. And then they had a child, June Streeter, that lived with Dale Sharp, if you remember, for a long time.

Wayne: Yeah, vaguely.

Milo: But – and then she stayed with the Streeters in Ogden most of her life, June did. And then the war broke out, World War I. Mark Streeter, her husband, joined the army and left my mother, Ethel Ross, Sharp Ross Streeter, abandoned in Idaho without a husband with this daughter, and he never did return. So after so many years, my dad met my mother in Paul, Idaho at the store because the Ross had come there to work at the sugar factory from Virginia, the grandparents and the whole family, Phibbs and the whole – lot moving out, have a moved out down to there to try to get work. So that’s how my dad met my mother was in Paul, Idaho, because they had Streeters confectionery. And that’s (unintelligible).

Wayne: Did your mother have no contacts up at Paul? Were there Plain City people or-

Milo: That’s something I never did know because Uncle Ed Sharp never told me.

Wayne: Uh-huh.

Milo: See, I was – mother came back here after she married dad, Jack Ross, we lived down by Abe Maw’s in an old log cabin house.

Wayne: With your father and mother?

Milo: Yes, Jack and my mother, Ethel. And then mother got sick with childbirth. There was – here mother had Milo – well, she had June to start out with Streeter.

Wayne: With Streeter, yeah.

Milo Ross in Canada 1986

Milo: And then she had Milo, my name, Milo James Ross, with Jack Ross, dad. And then there was Paul Ross.

Wayne: Little Paul?

Milo: Paul Ross, the blond, he fell out of Ed Sharp’s barn, broke his arm, fell on his head and concussion and he died when he was about 11 or 12 years old.

Wayne: I remember that, yeah.

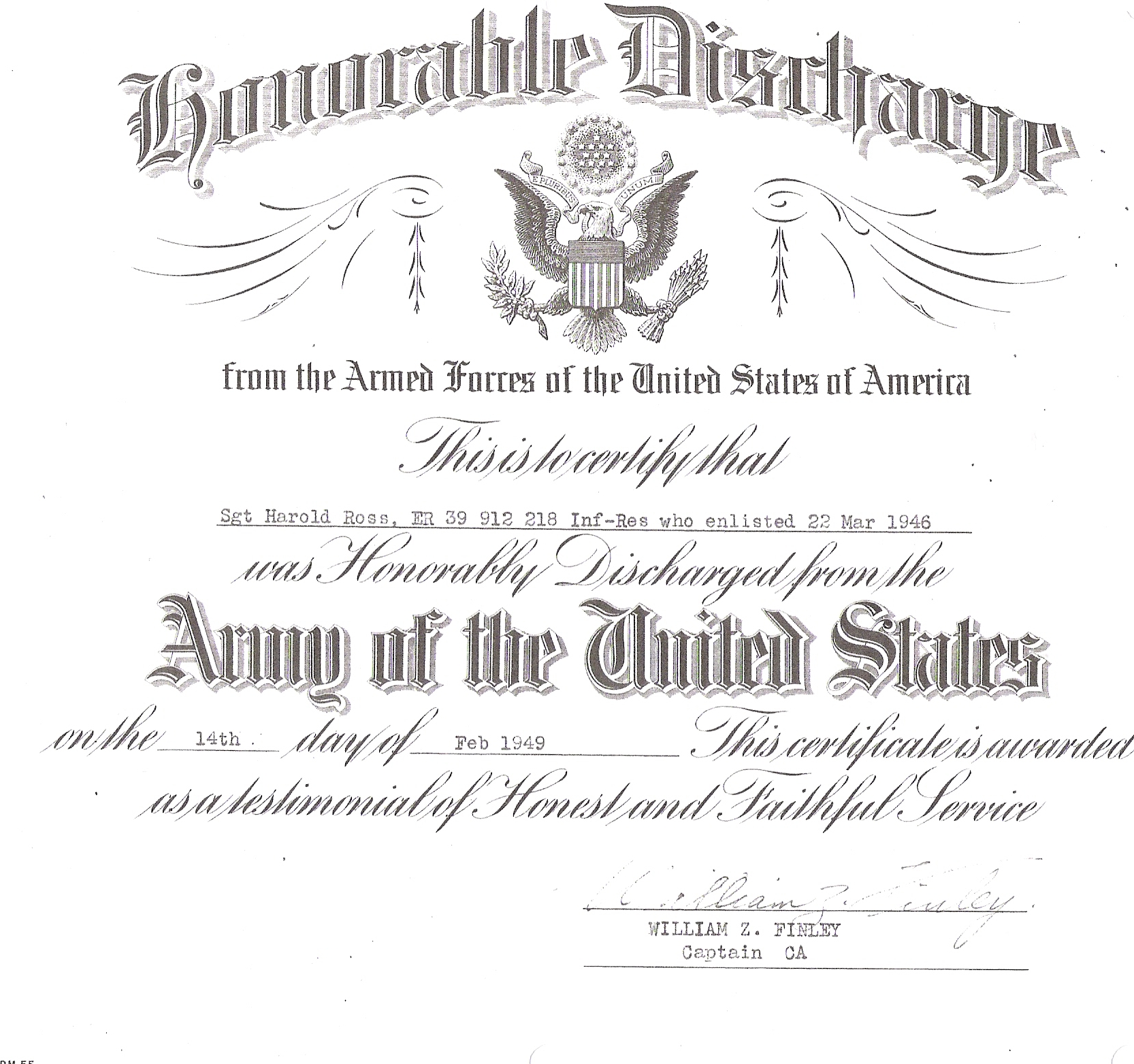

Milo: And that was up at Ed Sharp’s barn. Then there was Harold Ross, and then baby John Ross. But John Ross died at childbirth with female trouble. And that was down in Abe Maw’s property where the old log cabin house was.

And then when Mother died, my Dad, he had no way of feeding us down here because he’d come from Idaho down here with her to come back to live in Utah around her folks. They decided to – he didn’t’ know what to do. He couldn’t feed us. So he went to each one of the Sharps families and Os Richardson ad everybody else and they said they wouldn’t help him.

Wayne: Os had married Mary—

Milo: Mary –

Wayne: –yeah.

Milo: — Sister to Ethel.

Wayne: Mary Sharp.

Milo: So – and Ray Sharp, he didn’t want us. Over in Clinton.

Wayne: Oh, I didn’t know him.

Milo: Well, he was Ed Sharp’s brother. There was Ed Sharp, lived out here, and Dale Sharp.

Wayne: Right.

Milo: But it was hard times for everybody. They didn’t have no money to feed nobody extra.

Wayne: This would be in the twenties?

Milo: That would be back in nineteen twenty – I was born in ’21 and I was five when I come back here, when they brought – the Sharps brought us back here from going back to Idaho. But when I was five, my dad took us to the hot springs and carried us kids – took us to the hot springs, and put us on an old – I don’t know whether the church built a railroad track into Idaho or not. But they got on a dummy or a car and they went into Paul, Idaho, from the hot springs at that time.

Wayne: And you went up on that?

Milo: Yes.

Wayne: And –

Milo: My dad?

Wayne: — Harold.

Milo: — Harold.

Wayne: And Paul.

Milo: And Paul.

Wayne: And you went back up to Paul?

Milo: Paul, Idaho. I was – I was in the neighborhood about four years old at that time when he took us back.

Wayne: Now, he went with you?

Milo: He took us back there because dad – Grandpa and Grandma lived in Paul or Rupert, right in that area.

Wayne: Grandpa and Grandma –

Milo: Ross.

Wayne: –Ross?

Milo: Ross.

Wayne: Okay, yeah.

Milo: And they was from – Where’d I tell you?

Wayne: Virginia:

Milo: Virginia.

Wayne: Uh-huh. And how long did you live up there?

Milo: About a year. But you see, there was no money to feed kids. They couldn’t buy groceries and stuff. They came out here poor people.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: And they was working at the railroad – sugar factory trying to make a dollar. And Mother, she figured maybe send the kids – when she got sick, send them back up to Grandpa and Grandma. And see, Grandpa and Grandma was old and they couldn’t take care of us, so she – she just couldn’t make a go of it with the store and because she was sick, you know, with childbirth. And then they – I don’t know what they done with the store and everything back up there, but it really wasn’t a lot, but still it was a place they was making a little money.

Wayne: But had your mom passed away by –

Milo: Yes.

Wayne: – – When you went back?

Milo: Yes.

Wayne: Did she die down here?

Milo: She died in the log cabin house.

Wayne: So she’s buried in the Plain City Cemetery?

Milo: Right on Ed Sharp’s lots next to Ed Sharp and his wife. (Telephone rings.) Let me catch that.

Wayne: Can I borrow – –

(Pause in Tape.)

Milo: … Ross and gas station there at five points. And this is his boy, Nick Kuntz, married this Rhees girl and the lived right across the street.

Wayne: I probably know her aunts and uncles up in Pleasant View.

Milo: Yeah.

Wayne: Beth and – –

Milo: Yeah.

Wayne: – -Dorothy and – –

Milo: See, her dad helped build these homes here for Jones when they built this housing unit when they bought that ground from Blanch Estate there.

Wayne: Oh, the Wheeler – –

Milo: Wheeler Estate.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: But I was telling you about my mother.

Wayne: Yeah

Milo: Go ahead and tell me what you want.

Wayne: No, that’s fine because I don’t know this story. Harold told me some of it years ago, but – –

Milo: But – – are you still on tape?

Wayne: Uh-huh.

Milo: I’ll tell you a little bit more about dad and mother. My dad, he always walked to work. They had no cars then. They had horses and buggies and that’s about all. And he walked from Plain City over to Wilson Lane to work at the sugar factory.

Wayne: Oh, yeah.

Milo: And let Folkman – –

Wayne: Uh-huh.

Milo: – – Mark Folkman, them guys used to walk through the fields to Wilson Lane every day.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: Or ride a horse.

Wayne: Yeah, that’s four miles or so.

Milo: Four or five, yeah.

Wayne: Four or five, yeah.

Milo: Used to go over there to work at the sugar factory.

Wayne: Yeah

Milo: And whenever they come home or anything like that, they’d bring groceries and stuff home and carry it, you know, they – – nobody had transportation at that time. But it was tough for everybody. You don’t – – you talk about money, there was no money. They used – – they used scrip money, you remember, for a long time they give them kind of a paper money. If you took a veal or something to town, they’d give you scrip money for it, and then you could trade it back for groceries.

Wayne: Can you remember the scrip money?

Milo: Yes.

Wayne: I don’t think I can.

Milo: I’ve got – – I’ve got some papers and stuff like the stamps they used to save, sugar stamps and stuff – –

Wayne: During the war.

Milo: During the war – –

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: – – You had to have a stamp and stuff like that.

Wayne: Remember those tax tokens:

Milo: I saved – –

Wayne: Plastic – –

Milo: I tacked some of them with a hole in them, you know.

Wayne: Yeah

Milo: They called them Governor Blood money or something, your dad did – –

Wayne: Yeah

Milo: – – Mr. Carver. But there was no money for nobody around the country. And my Dad tried to feed us kids when we went back to Idaho wit Grandpa and Grandma. And they was – – they was probably like some of us today, didn’t have shoes – –

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: – – You know what I mean?

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: Hard going.

Wayne: Did your Dad go back with you to Paul

Milo: He rode back to Paul and stayed back there. He worked at the sugar factory for a long time with Grandpa.

Wayne: Uh – huh

Milo: And the Phibbs, there used to be a Judge Phibbs that married into the Ross Family. And they stayed in that area there for a long time. But I’ve – – my son now, Paul Ross, Milo Paul Ross, he’s – – he lives in Paul, Idaho.

Wayne: Oh, does he?

Milo: And it’s quite a coincidence, you know, and – –

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: – – I went back and I was gonna try to buy the building, one thing another, but it’s so hard to get the records and everything. But I do have the records and plot plan and some papers of my mother’s.

Wayne: Is the old store building – –

Milo: The old – –

Wayne: – – Still there?

Milo: The old store is there. I wanted to try to buy it, but Paul, Idaho, wants to restore the – – that street. Kind of run down, dilapidated, you know. They don’t wanna do anything right now until they get the money to go ahead and do things like that with it. But my dad called and said for the Sharps to come and get the boys because they couldn’t feed us. So that’s why Ed Sharp, Dale Sharp, and Fred Hunt, Aunt Vic Hunt, they took each one of us a kid. Ed Sharp took me Milo.

Wayne: Uh – huh.

Milo: Dale Sharp took Harold.

Wayne: Right.

Milo: And Fred Hunt, that would be Aunt Vic, my mother’s sister, Vic Hunt, they took Paul. And then June, she stayed with the Streeters all the time.

Wayne: Now, they’re in Ogden.

Milo: In Ogden.

Wayne: Uh – huh

Milo: So that’s how – – that’s why June didn’t stay here with us all the time.

Wayne: Now, this Streeter business, did – – Mark you say disappeared.

Milo: Right.

Wayne: Did he never come back?

Milo: He came back later on in years. He went as prisoner – – He went A.W.O.L.

Wayne: Uh – huh.

Milo: Do you understand me?

Wayne: Yeah

Milo: They called him a traitor of the country. They figured he spied against the United States.

Wayne: Was he overseas?

Milo: I don’t know.

Wayne: Good heavens, I – –

Milo: But, you know, you hear these stories.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: And then in World War II, he done the same thing. He collaborated with the Japanese out of San Francisco, see.

Wayne: Good Lord.

Milo: Yeah, Mark Streeter. But he says he didn’t, but he did. You understand me?

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: He – – He seemed like he always had his nose with the enemy. You understand what I mean?

Wayne: Yeah

Milo: Trying to make money that way.

Wayne: What did he do to make a living when he came back?

Milo: He’s just a dog catcher, something, picked up side jobs, Mark Streeter.

Wayne: Of course mother had divorced him then – –

Milo: right.

Wayne: – – on grounds of desertion.

Milo: desertion.

Wayne: Okay

Milo: That’s why she married my Dad.

Wayne: Right.

Milo: But, see, Dad called the Sharps and asked them to come and get the kids. So that would be in the wintertime they come and got us, and Ed Sharp took me, Fred Hunt took Paul, Dale Sharp took Harold.

Wayne: And June?

Milo: Stayed with the Streeters.

Wayne: In Ogden.

Milo: Grandma Streeter.

Wayne: And she was – – she was a Streeter. Her father had been Mark Streeter.

Milo: My sister is a Streeter. I’m a Ross.

Wayne: Right.

Milo: We’re half.

Wayne: Yeah. Is – – is June still alive?

Milo: June’s still alive. She lives down in California.

Wayne: I don’t think I ever knew her, but I’m sure she was in Plain City a lot.

Milo: She stayed around with Fern Sharp all the time.

Wayne: Oh.

Milo: They used to come out and stay there. And – –

Wayne: When she went – – when she came down from Paul and you guys went to the Sharps, she went – – did she stay with Mark Streeter then her father.

Milo: Mark Streeter’s mother.

Wayne: Oh, not with Mark?

Milo: Well, Mark Streeter lived with his mother.

Wayne: Oh.

Milo: Do you understand it?

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: And, oh, you remember Christensen, lives down by the store.

Wayne: Pub?

Milo: Yeah

Wayne: And Cap – –

Milo: He – – he lived down below Jack’s garage. But he had a brother that lived up by – – Ralph Taylor lives there now.

Wayne: Well, Cap Christensen – –

Milo: Cap Christensen.

Wayne: A – – (Unintelligible)

Milo: That was Cap, wasn’t it?

Wayne: Yeah, that was Cap.

Milo: Yeah. But you see, they had a daughter, would be Harold Christensen and – –

Wayne: And Max.

Milo: Max and all them – –

Wayne: Artell.

Milo: Artell.

Wayne: (Unintelligible)

Milo: Artell used to run around with my sister, June, and Fern Sharp – –

Wayne: Oh.

Milo: – – The three of them. You probably remember them together.

Wayne: I just spent an afternoon with Fern.

Milo: Did you?

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: Fern Sharp?

Wayne: Yeah. Shields.

Milo: Yeah

Wayne: Well, I’ve got that straight at last then. But do you know how long Mark Streeter was away before he came back?

Milo: Mark Streeter must have been away about four, five years, a deserter of the country.

Wayne: I wonder what he did in those – –

Milo: They – – they figured he was a traitor to the United States.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: But he said he was sick in the hospital. They – – I really never did know.

Wayne: Yeah. I wonder if anyone does.

Milo: The only way you could ever find out would be to go through court records.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: Weber County.

Wayne: Yeah. Okay. So that you’re with Ed, Paul’s with – –

Milo: Fred and Vic.

Wayne: – – Fred and Vic, and Harold’s with Dale and – –

Milo: Violet. She was – –

Wayne: Violet.

Milo: Her name was Violet Grieves before she married Sharp.

Wayne: Oh.

Milo: She’d be related to Pete Grieve and them.

Wayne: Uh – huh

Milo: And they would be related to the Easts in Warren. And Ed Sharp’s wife was East from Warren.

Wayne: She was.

Milo: So see, there’s kind of a – –

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: – – Intermarriage through the – – each family down through that line down – – but when Dad told the Sharps to come and get us out of Idaho, they came up to get us. And I was about five years old when they come. And before – – before we was ready to come home to Utah again, us kids was playing in bed and I got a – – a fishhook caught in the bottom part of my eyelid here.

Wayne: Good Lord.

Milo: And I was only maybe five years old and – –

Wayne: yeah.

Milo: – – I remembered it. And I can remember my Grandpa telling me, do not pull, leave it alone, leave it alone, and he said, I’ll have to get you some help. So, they went and got some help and these guys come back and I heard one of them say, you take his feet and I’ll take his arms. You know. And somebody else hold his head. So, what they done, they – – they – – I think they must have cut the hook or something and then reversed and took it out. I don’t know what they done. But it was caught in the bottom of my eyelid. But they – – I was sore of that when I come to Utah. And then when – – I don’t know whether Dale Sharp was with Os Richardson when they come up to get us or not. But they come up in a big car to Paul, Idaho, and they brought us home across the Snake River at Paul, between Paul and Rupert there someplace to bring us back home. And every so often, I’d look back and I – – I thought I could always see Grandpa and Grandma and my Dad waving goodbye to me.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: And farther down the road we got, it seemed like we were always stopping, the car had trouble or something, tires or something. Putting water in it and that this – –

Wayne: This is Os and Mary’s car.

Milo: Yes.

Wayne: Did Mary come up?

Milo: I don’t remember whether Aunt Mary was with us or not. I don’t remember who was in the car, but I do remember Os Richardson because he was kind of a heavyset man and he was quite blunt.

Wayne: Yeah, I remember him.

Milo: Yeah.

Wayne: He was our neighbor down at Warren.

Milo: Yeah

Wayne: Yeah

Milo: He was quite blunt. And he’s – – I figured him a mean man.

Wayne: Oh.

Milo: And when I’d wave, he’d also say, put your arm down, you know, don’t distract me, and this and that, you know.

Wayne: Yeah

Milo: But we rode in the back seat, but I’d look back and didn’t matter which hill. I could see my Grandpa and Grandma.

Wayne: Yeah. Yeah.

Milo: But it was quite an experience. We came home and they.

Wayne: How old you were then, Milo?

Milo: Five years old.

Wayne: Five.

Milo: But they – – they brought me back and give me to Ed Sharp. And they took Paul down and left him with Fred and Vic. And then they took Paul – – Harold down and give him with Dale Sharp. But I think Dale Sharp went us with us – – them to bring us back. And we were only within what, two or three blocks of each other, and yet I couldn’t go see him. They was afraid I’d run away.

Wayne: Oh

Milo: So I was kind of quarantined, you know, and you’ll get to see him on the weekend. You know, they was trying to separate us.

Wayne: Could be, yeah.

Milo: And when Paul come here, he had a hernia down right this side of his groin. And when he’d cough or sneeze, it’d pop open like a ball inside.

Wayne: He’s just a little boy.

Milo: Little boy. And it would pop open and they had kind of a – – like a leather strap or something around there and a pad around it to kind of hold it in – –

Wayne: A truss.

Milo: – – Truss or something.

Wayne: A trust, yeah.

Milo: But it was tough for us kids.

Wayne: I’ll bet it was tough.

Milo: It was tough.

Wayne: You – – you were the oldest.

Milo: I was the oldest, five.

Wayne: Five and – –

Milo: Four and three.

Wayne: Harold was four – –

Milo: Yeah.

Wayne: No, Harold was – –

Milo: Paul.

Wayne: Paul.

Milo: And Harold. Five, four, three.

Wayne: Five, four, three. Yeah and June was maybe six?

Milo: She was probably two years older than us.

Wayne: Uh-huh.

Milo: Three, I don’t remember just what.

Wayne: Did you ever see your dad – –

Milo: Yes, sir.

Wayne: – – Again:

Milo: After the war, I went into the service, World War II, and I received a letter from Livermore, California, and it stated that my Dad was a veteran, World War I, and he was in Livermore, California not expected to live over maybe a week, three, four days. And he would like to see one of his boys if they’d like to come and see him before he died. And the Sharps and everybody told me leave him alone because he was a no good man. He never cared about us.

Well, I’d married my wife, Gladys, and we had this son, Milo Paul, but her dad Donaldson says, “Heck, Milo, if you wanna go down see your dad,” he says, “I’ll give you the greyhound bus fair down. $55, $80, whatever it is.”

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: He said you’ll have to thumb your way back. I said, well, if I get down there I’ll get to see him, that’d be fine. I asked my wife, if it would be all right to go, and she said yes.

Wayne: Were you living in Plain City?

Milo: Living in Plain City. And we were renting at that time just a house, you know. And I says to Dale Sharp and them, I says, I thought maybe I’d go down and see my Dad. And they says, forget about him. Him he’s no good son of a bugger, you know, they called him by a name – –

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: – – So I decided to go and I went to Livermore, California, and I jumped a ride out with an army truck and to Livermore, California, Hospital. I got there late – –

Wayne: Was this an army hospital?

Milo: Yeah. Veterans’ Hospital, Livermore. And I got there late in the evening. And nothing was going around and nobody was doing anything, it was on the weekend. So I go into the hospital and nobody’s around so I just kind of walked through the – – it was late and maybe 1:00, 1:30 in the evening, night. And I walked down through the halls and went up on the second floor and walked down the aisle a little bit, and I thought, well, maybe what I better do is just sit here in the corner, and maybe have a catnap for a while. Then I heard somebody cough, and heard them say, “what time is it?” And somebody said, “it’s about 1:30, 2:00 o’clock,” see? So I heard this talking and I walked down the hall a ways and I seen the one light on one of the beds and I says – – stepped towards the door, and I says, “Does anybody happen to know a Jack Ross or anybody in here, is anybody here can hear me?” And a voice come back and it says, yes. “Come on in, Milo or Harold. I’m your Dad.”

Wayne: Oh, boy.

Milo: And I walked right to that man’s door.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: And It’s – – And about that time, two guys grab me by the arm and escorted me out of the room. And they gonna have me put in jail because he had no visitors. You understand me? He was on oxygen and this and that. So I says, “Oh, what difference does it make?” I said, “I’m his son. I don’t remember my dad.” I says “At least you could do is let me tell him goodbye. If he’s gonna die, what difference does it make?” So these two orderlies says, “you stay outside for a while.” So I stood there by the door and they hurried and they put some needles and stuff in his legs. Was probably giving him morphine or something. I don’t know what they were doing, trying to do keep him alive longer, something, I don’t know what they were doing. But I says to the one gentleman, he run past me fast, and I says, “Couldn’t I just say goodbye to my dad anyway?” And he said, “Well, just wait a while.” So pretty soon there was about three of them over my dad working with him, and finally the one young man says to the rest, he says, “Oh, let the kid come in and say goodbye to his dad.” So I walked in, talked to dad. He says, “I’m sure glad you come.” And I said, “Well, I’m Milo.” And I said, “I don’t remember you, Dad,” but I says, “I decided after reading the Red Cross letter I would come and see and you tell you hello. Tell you thanks for letting me have a Dad, anyway.”

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: So he says, “Well, Milo,” he said, “I’m gonna tell you a secret.” He says, “When I took you kids to Idaho, I was a son of a bitch.” Then he says, “When I got into Idaho, he says, I was a son of a bitch.” And he says, “It didn’t matter what I done, I was a son of a bitch.” He said, “Then they told me if I ever come back to see my kids after I sent you down to Utah, they would kill me.”

Wayne: The Sharps told him?

Milo: The Sharps. I says, “Which one of the Sharps?” And he says, “It’s best not to say, Milo.” But he says, “I’ll tell you secret, if you don’t think I ever come to see you, ask Betty Boothe.” He says, “You remember Betty Boothe?” And I said, “She’s been in my home, many, many, many times.” And he says, “I come out in a taxi cab three times, and I got Betty Boothe to go with me to see you kids.” And he said, “I rode out to Ed Sharp’s Farm and I didn’t dare get out of the taxi. Because I – – I was threatened I’d be killed.” So he says, “I did wave out of the taxicab and sit there and watch you out in the field,” us kids. And says, “If you don’t think I did,” he says, “ask Betty Boothe.” And then I got a different feeling towards my Dad – –

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: – – when he said that.

Wayne: Yeah, I can imagine.

Milo: Because I could see – – now I have letters that was sent to the Sharps and the Hunts and they hid the letters from us kids. They would not tell us that Dad and Grandpa sent us letters or anything. And I have these letters. And in these letters it’s Grandpa and Grandma asking please, tell us how the little kids are. And then my Dad, he wrote a letter and he says – –

Wayne: Now, were there – – they up in Paul all this time.

Milo: Paul, Idaho, all that time.

Wayne: Uh-huh.

Milo: But the Sharps and them, they’d never read us the letters and everything because they – – they wanted us to be with them. The Sharps and Hunt. Do you understand?

Wayne: Yeah, I understand.

Milo: Kind of hard – – but I have those letters.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: And when – –

Wayne: He was thinking about you a lot more than you thought he was.

Milo: Well, this is the bad part about life. Now, Aunt Vic Hunt, when Fred Hunt died, Howard Hunt got killed in the war, her son – –

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: – – Fred Hunt got – – died. Bert Hunt, their son, got electrocuted and Bob, the grandson, got electrocuted.

Wayne: I remember that.

Milo: The night before they got electrocuted, I helped Bert Hunt carry the milk from the barn to the milk parlor where Bert and his boy got electrocuted. And I helped carry that milk cans the same as they did the night before.

But Aunt Vic Hunt says, “Oh, Milo, she says, I just feel like I – – I’m being punished for something.” She says, “I’ve got a box here that came from you folks.” And she says, “I’ve got all these letters and everything.” She says, “I’ve read them. And I’ve never told you about them.” But she says, “I’m not gonna give them all to you now, but I will give you some of them.” So she give me some of the letters. And she had kind of an old cigar box. Remember the old cigars boxes with a lid on it? And she says, “I’ll give you this, too.” She says, “I think maybe I’ve been punished long enough now.” She says, “I’ve lost too many in my family. Maybe I’m being punished because I haven’t been fair to you kids.” She says, “Here’s the box, the gifts and everything they’ve sent to you.” I says, “Aunt Vic, if that means that much to you,” I says, “You keep the box. And then when you’re dead and gone, you tell your family to give it to me.” But I says, “I will take these letters. And I sure love you for it. And thanks for being good to us kids.” And I says, “Gladys and I will go now.” My wife was with me. She was really brokenhearted. I told her she was forgiven and everything. I says, “Live you life out.” I done a lot a work for aunt Vic after that. Helped her wire the house and anything went wrong, I’d go help her, help her, help her, help her, help her.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: But when she – – she died, the family never did give me the cigar box of stuff back. They kept it. And I think today Archie Hunt probably has it.

Wayne: Now who would – – who is he?

Milo: That would be Vic Hunt’s boy, grandson. Bret Hunt – –

Wayne: Oh.

Milo: – – That got electrocuted. This is my wife and daughter, if you’d shut that off a second I’ll help them.

(pause in the tape.)

Milo: The letters and stuff that my wife and I got from my aunt Vic Hunt. And when I read them, I – – I felt a lot better towards my dad and my family because it’s – – they wanted to separate from us that Ross family altogether. But I have an old, old bible on the Ross side that’s a great big hardback bible from Virginia. And I have a half-brother back there. And my dad had married a day lady back there. When my mother died, he went back to Virginia to see if he could make ends meet to bring the family maybe to Virginia. But he couldn’t make a go of it with the day. And this son of his, Hobart Day, he told him about having a family here, Milo, Paul, and Harold, and John that died. Well, all these years, Hobart, the half-brother back there, instead of keeping the Ross family, he kept the Day family. So he kept the old bibles and everything back Virginia at the home back there. So I got Hobart, after I made contact with him after doing genealogy work after the war, then he – – I bought his way out here, him and his wife out here twice to visit with us. And he brought this old, old bible out here and it’s one of the King James, I’d say it’s about five, six inches deep, hardback. You’ve probably seen them.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: Yeah.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: But I that have of the Ross Family there, but it’s quite a deal, you know.

Wayne: Did you ever see your Ross grandparents?

Milo: Not after. See, they were old and feeble.

Wayne: Uh-huh.

Milo: I never even got to go to their funeral. That’s what makes it bad. But my brother, Harold Ross, his wife, Colleen Hancock, she done a lot of genealogy work and she’s the one that got us together on genealogy to get the Ross family back to Virginia.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: And Hobart Day, the half-brother.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: But it’s – – and then I have – – I have my grandparents’ old china cabinet. And I have the old wooden washing machine. And I have the old cream separator they used to turn the handle on.

Wayne: Now, Which grandparents?

Milo: The Ross and the Sharps.

Wayne: After the – – your Ross grandparents passed away?

Milo: Yeah.

Wayne: And Paul.

Milo: Yeah, I’ve got part of their – –

Wayne: How did you get those – – That?

Milo: Through the – – through the people in Idaho.

Wayne: Uh-huh.

Milo: See, they – – they set them aside.

Wayne: In the ward – – well, they weren’t church members, were they?

Milo: No. They were Presbyterians. They were not LDS. But I have this old wooden wash machine. I’ve recent – – redone it and put it together. Made new stays for it so every part works on it and all the metal.

Wayne: Did you go up and bring them back?

Milo: No, they were given to me from Paul or Rupert, Idaho. On the Phibbs side family or something like that.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: So I do have – – And then on the Grandma Sharp side, I have parts of her old stuff, too, books and stuff. I have my mother’s records of Paul, Idaho store where they – – where they sold eggs, a dozen eggs like for two and a half, three cents.

Wayne: A dozen.

Milo: A dozen.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: Yeah. They – – It’s amazing. I have – – I have a lot of old antiques and stuff. Before you leave, I’ll show you lot of my old antiques and let you see the washer and stuff like that.

Wayne: I’d like to see that.

Milo: Then maybe someday you’d like to come by and take a picture or of them or something. Or you can talk to them – – while we’re looking at them, talk to us.

Wayne: While we’re on family, your mother was a Sharp.

Milo: Ethel Sharp. Her dad was – – they lived where Ernie Sharp lived. Milo Sharp.

Wayne: Oh, yes. Now, was it Milo – – Milo Sharp was one of them group that separated from the church, was he not? And they became Episcopalians.

Milo: Right.

Wayne: Do you know anything about the cause of that split?

Milo: One Bishop.

Wayne: Really: I’ve not been able to pinpoint it.

Milo: The way I understand it, they – – they asked them to pay a tenth of the tithing of everything. And he – – he told them if they killed a beef, he wanted a certain part of that beef.

Wayne: The Bishop told them?

Milo: The Bishop.

Wayne: Do you know who the Bishop was?

Milo: I think Thatcher. Does that sound right?

Wayne: That sounds too late. Gil Thatcher was Bishop, we’re back in 1869 and ’70 when this Schism, this Split, so it wasn’t Gil Thatcher.

Milo: Well, I don’t know for sure.

Wayne: Shurtliff, maybe.

Milo: I was back in that area. But the Bishop at that time, the Hunts excommunicated from the church also. Fred Hunt, Vic Hunt, all them, they went to Episcopal Church.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: They build the Episcopal church down by Dean Baker’s there. They use that for the Lions Club now.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: My mother used to be the organist for it for many years, they said.

Wayne: Your mother Ross?

Milo: Uh-huh. But she was a Sharp, Ethel Sharp.

Wayne: Of course, Sharp.

Milo: She was a Sharp. She played the organ for them when she was younger. And she played the organ and kind of led the music and everything like that.

Wayne: You know, Vic didn’t know for sure what had caused – – it was her father, Milo.

Milo: Right, Milo.

Wayne: And he – – she said, oh, Wayne, they liked their – – to play cards and they did a lot of things that church didn’t like and they just finally got tired of it. But I think there was some – – something somewhere.

Milo: It was over – – it was over the meat. Dale Sharp – –

Wayne: Uh – huh.

Milo: – – Took care of Harold and Ed Sharp took care of me. And Ed Sharp gave the church an awful lot. He used give them the asparagus, he used to give them potatoes. When they harvest or anything like that, he’d say, Bishop Heslop, Bishop Maw, whoever the Bishop was, come up and get sacks of stuff for some of the people. But Ed Sharp and them, they always give to the Mormon church.

Now, when they built the Plain City church down here, they used to sell cakes and stuff, raffles.

Wayne: The new one?

Milo: The new one.

Wayne: That’s gonna be torn down.

Milo: Yeah, but I – – see, I helped build that. I was a carpenter on it and Lee Carver was the supervisor on it. And I was – – George Knight was the Bishop on it. But when they auctioned these cakes and that off, Fred Hunt was probably one of the ones that bought the cakes probably more than anybody. He probably paid four, five hundred dollars for a cake.

Wayne: Yeah, yeah.

Milo: So you see, it wasn’t religion against religion because they did – –

Wayne: Not by that time.

Milo: – – They were together.

Wayne: Uh-huh.

Milo: But the earlier Sharps and some of them, And I think some of the Taylors pulled away from the church, too – –

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: – – And they went farther east.

Wayne: The Thomases.

Milo: Thomases, they pushed out, too, on account.

Wayne: But then they slowly worked back.

Milo: Come back in.

Wayne: Yeah. As a little guy then living in a family that was not LDS – –

Milo: Right.

Wayne: – – What was your religious upbringing, Milo?

Milo: Never had much. We did go to church.

Wayne: To the LDS?

Milo: No.

Wayne: Or to the Episcopalian?

Milo: Episcopalian – –

Wayne: Really.

Milo: When we went to Idaho, see, they didn’t have a Mormon church there. See, the Presbyterian, whatever it is. But I’ve got some of my mother’s song books and stuff, some of the old songs books.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: They sing the same songs there as we do today in our church.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: It’s kind of nice.

Wayne: I can remember as a kid, we would hear the bell ring, the bells – –

Milo: Yes.

Wayne: – – Ring, and we’d run down to the end of the lane – –

Milo: To look at it.

Wayne: – – And look at the people going to church.

Milo: Uh-huh.

Wayne: But that – – those were – – those were only maybe once a month or whenever the minister could come out – –

Milo: Yes.

Wayne: – – From Ogden. And that someone told me, I think, oh, Leslie’s wife, Ruth – –

Milo: Yeah.

Wayne: – – Poulson, that there was a lady lived out in Plain City, lived in that house where Leslie and Ruth lived, who was kind of she – – the representative of the Episcopalian Church, and she taught school.

Milo: Uh-hu.

Wayne: Did you go to that school?

Milo: I didn’t.

Wayne: Might not have been around when you – –

Milo: If you reach down there to your right side down there’s a little tiny book right there.

Wayne: This one?

Milo: I got a lot of little books like that. That book right there came from Huntsville. That came from the Joseph Peterson’s library in Huntsville probably, huh?

Wayne: Yeah, yeah.

Milo: But I’ve got – – I pick up all these books and stuff like this when I’m out around traveling, and I buy them and get them.

Wayne: Yeah

Milo: Now, I’ve got a lot of books like this and I’ve got a lot of mother’s books and stuff where she’s wrote poetry and stuff. My mother wrote a lot of poetry. And Albert Sharp got almost all the poetry and everything of my mother’s. So if you got on the Sharp – –

Wayne: I did talk to Albert, but I didn’t see any of your mother’s poetry.

Milo: She wrote a lot of poetry.

Wayne: Uh-huh. Well, that was probably true of Harold growing up with Dale Sharp – –

Milo: Non Mormons.

Wayne: But Harold went to Mutual with us.

Milo: We went to Mutual.

Wayne: You went to Mutual.

Milo: I went to Mutual.

Wayne: Uh-huh. And Harold became a member of the LDS Church.

Milo: Right. So did I later.

Wayne: Do you know – –

(End of Tape I-A.)

Wayne: …Of a conversation with Milo Ross in Plain City.

Milo: See, when we were – – When we went to school, we – – they’d always ask us to go to Sunday School or Mutual or whatever they had.

Wayne: Primary.

Milo: Primary.

Wayne: Did you go across the square – –

Milo: Yes.

Wayne: – – to – –

Milo: Yeah, we always – – he went anyway.

Wayne: Sure.

Milo: You know, because everybody kind of went together. Then we went to Weber High. I took Seminary.

Wayne: You did?

Milo: So – – well, Ruth took Seminary too. Your sister, Ruth.

Wayne: Oh sure. So did I.

Milo: So we took – – we took Seminary – –

Wayne: Floyd Eyre.

Milo: – – Together. We took seminary from Mr. Eyre, he was the principal, he was the teacher of it. But, you know, I enjoyed – – I enjoyed listening to the stories. Then I enjoyed taking the assignments, reading certain scriptures and things that they give us.

At that time, they did not press the Book of Mormon like they do now.

Wayne: No, I think that’s true.

Milo: See, And – – But I enjoyed it.

Wayne: And Ernie didn’t object to this?

Milo: Nobody ever – – nobody ever objected to anything.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: It’s like the Martinis and the Ropalatos in West Weber, I’ve done a lot of building for them. The old grandpa and grandma and them guys, you’re not gonna convert them, but you see the young girls and the young boys are joining the Mormon church.

Wayne: Uh-huh, yeah.

Milo: See, the Martini girls marries the Dickemores that’s Mormons. So see they – – but the old – –

Turn that off just a minute.

(Tape pauses.)

Milo: …Truck – – truck and trailer all loaded. And I seen aunt Vic get hit. She came up to the stop sign from the west side and she stopped. And then she went to go across the road, and when she went to go across the road, there was a car came from the north, I’d say hundred miles an hour, some young girl. And the young girl was gonna pass her on the front as aunt Vic went ahead. She throwed on her brakes a little tiny bit and she got caught Aunt Vic back, just back of the door, back of her car. And that throwed Aunt Vic’s car around in a spin and the young girl come right on down to where I was at watching it.

Wayne: Where were you?

Milo: I come from the south. And see I – – I seen it all.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: Well, I knew it was Aunt Vic’s car, and this young girl, she come down to road, and she was unconscious laying over the steering wheel. And she come down the road, so I pulled off the side the road so that she wouldn’t hit me, then she made kind of a slump over on the wheel and she pulled to the right side and got off the side the road and that’s where her car stopped. So I opened the door there and a kid come up on a motorcycle and I said, run back down to the store on your bike, motorbike, and get some ice and let’s put on her and see if we can revive her. So the kid, he went back and got ice and the called the cops and that. I told them to call the cops. And he come back with this bag of ice and I was putting ice and that on when policeman came, and she came to by that time.

Wayne: Now, is this the young girl or Vic?

Milo: The young girl.

Wayne: Oh. Where’s Vic all this time?

Milo: She was up at the intersection about 50 – – oh, a hundred, hundred feet farther up the road.

Wayne: In her car.

Milo: In her car. But she had spun around and she had went on the east side of the road facing south.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: It spun her completely around.

Wayne: Didn’t tip over.

Milo: Didn’t tip over. But I seen it.

Wayne: Yeah. Her sister Mary was with her – –

Milo: Yes.

Wayne: – – That day, I talked – – and I did – – I asked Vic what was it like growing up in Plain City as a not only a non Mormon, but as the daughter of one of the ringleaders in the separation. And she said, oh, made no difference. She said, I never had any prejudice. And Mary wouldn’t agree with her. Mary said they looked down on us.

Did you ever have any sense of being looked down on because you were not a member of the church?

Milo: I don’t think anybody ever looked on any of us.

Wayne: Did you hear Vic or Dale or any – – or Ed – –

Milo: Nobody ever – – nobody ever looked down on the church.

Wayne: Did the church look down on them?

Milo: I don’t think so.

Wayne: Dad was a great friend of Ed’s.

Milo: Every – – they were the closest buddies in the world.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: And Joe Singleton.

Wayne: Uh-huh.

Milo: You dad and Ed Sharp and Joe Singleton was probably the first appraisers and supervisors of the home loan administration or something like that, weren’t they?

Wayne: Dad as a – – worked for the assessor’s office.

Milo: Okay.

Wayne: In Weber County.

Milo: That’s why they got Ed Sharp and Joe Singleton to work with him then.

Wayne: Oh, I guess, yeah.

Milo: But they went around and appraised property and one thin another, when these guys was trying to get home loans for farms and stuff.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: Now, when they got the loans and stuff like that, they got them on a loan, real low interest rate. And then when they settled my grandmother Sharp’s estate and one thing another, my estate money from my mother’s side, us kids being young, they decided instead of giving us kids the money, the one that was taking care of us would get the money and they could put – – apply it on their home loan – –

Wayne: Oh.

Milo: – – To keep their farms because a lot of people was losing their farms because a lot of people was losing their farms at that time.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: Mr. England and some of them had lost their farms, you know, and the Maws and some of them, they’d – – that’s when the banks went broke.

Wayne: Right.

Milo: And so when they settled the estate and one thing anther, my share went to Ed Sharp. And Harold’s share of his when the split it up amongst us kids went to Dal Sharp. And Fred Hunt took Paul’s share, see?

Wayne: Right.

Milo: And they applied that to their home loans. To keep them from losing their farms. Then after Ed Sharp, these guys die, Vic settled the Sharp Estate on their side, Ed Sharp’s Estate, and Ed Sharp’s girls and boys, they didn’t wanna pay me back the loan that they had taken from me as a youngster. They said I wasn’t entitled to it because I hadn’t applied for it. You know, they go back to the legal deal.

Wayne: Yeah, yeah.

Milo: So I says, well. I’m not gonna fight nobody. But I said,tell you what I’d like you to do. Why don’t you just pay me four or five percent interest on it all those years.

Wayne: Just give you the interest.

Milo: Yeah, but it was kind of a sore thumb.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: I told them I don’t care.

Wayne: It was a loan that you had made without knowing it.

Milo: I – – I didn’t know anything about it.

Wayne: Right. That’s an odd way of handling that, you know, anyway – –

Milo: Well – –

Wayne: – – If it should have been put in a trust of some sort and the – – so you would be sure to get it.

Milo: I didn’t really want it because I helped my uncle Ed save his farm that raised me, you understand?

Wayne: Uh-huh.

Milo: So I – – I said, oh, he was good enough to give me a home, I don’t care.

Wayne: Just to – p for the tape and to jog my memory, who were Ed’s kids? I remember liking – – there was Ruby.

Milo: Louise, start with Louise.

Wayne: Okay. She the oldest.

Milo: Louise.

Wayne: Louise.

Milo: She married Ralph Blanch.

Wayne: Oh, okay.

Milo: Florence, married Nielson.

Wayne: From Taylor?

Milo: West Weber, Taylor.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: Leonard Nielson.

Wayne: Did he used to pitch.

Milo: Yeah.

Wayne: Yeah, stiff-armed and – –

Milo: Yeah. And then there was Marjorie, she married Ferrel Clontz, big tall guy, went to Idaho.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: Then there was Ethel Sharp.

Wayne: I remember Ethel.

Milo: She married Garth Hunter. Then there was Ruby Sharp. She married Norton Salberg. There was Milo Sharp. You remember Milo Sharp.

Wayne: Mutt?

Milo: Mutt Sharp.

Wayne: Okay.

Milo: That’s Milo.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: And then there was Dean Sharp – – no, there was Josephine.

Wayne: Josephine.

Milo: Josephine Sharp, she married Darwin Costley, Paul Costley’s brother.

Wayne: uh-huh.

Milo: Then Dean Sharp, the baby.

Wayne: Dean.

Milo: Dean Sharp. And Louise took care of Dean when Ed’s wife passed away.

Wayne: Oh, who was Ed’s wife.

Milo: She was Lilly East.

Wayne: Right, okay. From Warren.

Milo: From Warren.

Wayne: Yeah?

Milo: Yeah

Wayne: So there were two Milos in your house.

Milo: Both Milo, Milo Ross and Milo Sharp.

Wayne: Right.

Milo: I was older. Now, they had another son, Elmer Sharp, that died young with scarlet fever or something, around 12 or 13 years old, but I don’t remember him. When we were kids at that – – living with Ed Sharp’s at that time, they had diphtheria, they had different things that they used to have this doctor that used to come out, Dr. Brown or somebody, and they’d always give us a shot and medicines and stuff, you know.

Wayne: Yeah. So how – – you were – – you were five when you went to live with Ed?

Milo: I was five when they brought me back down here to live with Ed Sharp, five.

Wayne: So those kids were your brothers and sisters in effect.

Milo: Not that close.

Wayne: Weren’t you?

Milo: Un-unh. They always – – I don’t know, they – – they felt like Ed Sharp showed me a little more prejudice or something. When he got his truck, I got to jump in the truck and go with him once in a while to feed the cattle and stuff, do you understand that?

Wayne: Uh-huh.

Milo: Then had he his truck and he’d – – he’d get the neighbors they’d all get in the truck and go for rides and camp overnight up in the canyons. And they used to go down to Warren, pick up the Easts and Caulders. And they used to get in this truck and they’d go up to Pineview Dam, up to the wells – –

Wayne: Uh-huh.

Milo: And they’d stay overnight.

Wayne: The old artesian wells.

Milo: Uh-huh.

Wayne: Yeah, before the dam.

Milo: And Jack Singleton, do you remember him?

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: Now, Ed Sharp, he had a salt mine out at Promontory. And he used to – – he used to run that through the winter and harvest salt. And I was with Ed Sharp – – you got a couple minutes: I was with Ed Sharp once when we was coming back with a load of salt from Promontory up on the hill, and there was a place there we always stop and get a drink. And there was a note there. And Uncle Ed read it and this Charlie Carter, and old hermit out there, that used to prospect, mine, and one thing another, decided to end his life so he jumped down in the well and killed himself. So Ed Sharp and I went down the railroad to Promontory, and Uncle Ed had them – – done something on teletype or wherever you call it, code, and they sent a message back to Brigham City to Sheriff Hyde, and he came out and told us to stay there until he came back out. But they – – they took ropes and everything and lowered lanterns down in this here well. When they’d get down so far where uncle Ed was down there trying to tie the rope around Charlie Carter, these lamps would go out. No oxygen, I guess – –

Wayne: yeah.

Milo: So – –

Wayne: But body was there, huh?

Milo: It was down in there.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: But Uncle Ed Sharp, after he went down in there and tried it a few times, the lights would keep going out, they said, well, we – – there’s no use putting down anymore because they’re gonna go out all the time. But Charlie Carter, he came out there, the Sheriff, and he had somebody with him. But Ed Sharp, he went down – –

Wayne: Not Charlie Carter, he’s the body. Hyde.

Milo: Hyde.

Wayne: Right.

Milo: But he went down, Ed Sharp went down in the bottom to get Charlie out, Tie a rope on him, get him our if he could. And we let the ropes down and then when Ed Sharp pulled on the rope or this or that, they could holler down and talk to him. It was a deep well. And they tied these ropes together three or four times, lowered him down in there and – – and finally they signaled, and they said, help us pull. So, I was a little tot, maybe 14, 15. I really don’t remember, but I remember helping pull on this here rope, and they worked a long time to get him up out of the well. Then when we get him right just up here to the top of the well to get him up of there, we couldn’t get him out over the well. And somebody jumped up on that wooden platform there and took a hold of him and helped pull him out and over. And Ed Sharp was underneath him, helped pushed him up out, dead Carter. They pushed him out on the ground and he just kind of flopped out there on the ground where we were at. And these – – Hyde and his friend took a hold of Ed Sharp and helped him out of the well, they untied the ropes from around his body because they – – If anything went wrong, we could pull him back up. And soon as he got out on the ground, he went into a cold shock because he’d been down in that cold water. And when he – – he started to shake and tremble and just – – he couldn’t control the nerves in his body. And they made Ed Sharp lay down on the ground and they took his clothes off and they took blankets and gunny sacks and stuff and rubbed him and rubbed him and rubbed him and tried to circulate his blood or something. I don’t know I’d – – hardly what was the matter. I remember I was crying. But remember I was so scared and – – And when he got out, they laid him down like that, I got down and I give him a big love, you know, and I told him, I said, I’m sure glad you’re out of there, you know, I – I was scared and I – –

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: – – I’m sure glad – –

Wayne: How old were you?

Milo: I don’t know. I must have been about 12, 14, I don’t remember.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: But I was just thinking about it, and Mr. Hyde and that guy, they rubbed him and rubbed him and rubbed him. And they got him so he wasn’t trembling so much. And then they – – they changed clothes around from one to another so he could have some dry clothes on. But little things like that in life, you never forget it.

Wayne: No. Lord.

Milo: But see, nobody knows about Ed Sharp going down in the well and sav – –

Wayne: No.

Milo: – – Saving a dead man’s life and give him a burial.

Wayne: Right.

Milo: Now he wasn’t a Mormon.

Wayne: Well, he was dead.

Milo: He was dead.

Wayne: Didn’t safe his life. Saved the body.

Milo: Saved the body, but he give him – – he give him life, he give him burial.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: But you see now, he wasn’t Mormon.

Wayne: No.

Milo: But see, he went down in there – –

Wayne: What did Ed – – what did they do with the body.

Milo: Sheriff Hyde, they – – Sheriff Hyde had that – – looked kind of like a square – – like an old square Hudson or something, Graham or something, I don’t remember. An old square car. And we had to help them put him on – – put his Charlie Carter on the back seat. And they rolled him up in canvases, put him on the back seat and took him to Brigham.

Not long ago there was a piece in the paper about Mr. Hyde, they – – somebody wanted to get a little history about Sheriff Hyde, and I was just thinking, well, maybe I should let them people know that – –

Wayne: Right.

Milo: – – I was – –

Wayne: He was Sheriff up there for a long time.

Milo: And then his boy took over after that, they tell me.

Wayne: Oh, did he?

Milo: They tell me.

Wayne: Maybe that’s why – – wasn’t it Warren Hyde or – –

Milo: Warren, something like that.

Wayne: Yeah. I didn’t know about Ed’s salt operation.

Milo: That was one of the biggest in the state.

Wayne: Really?

Milo: Yeah. Then they opened that one up down towards Wendover. And see, they – –

Wayne: Ed did?

Milo: No. Morton Salt or somebody – –

Wayne: Oh, yeah, yeah.

Milo: – – opened up a big one down there. But we – – in the winter, they used to load boxcars, salt out – – out at promontory.

Wayne: Now, did Ed own this operation.

Milo: Ed Sharp and Ray Sharp. They took – –

Wayne: Who’s Ray.

Milo: A brother. Ed Sharp’s brother, Ray Sharp.

Wayne: He never lived in Plain City?

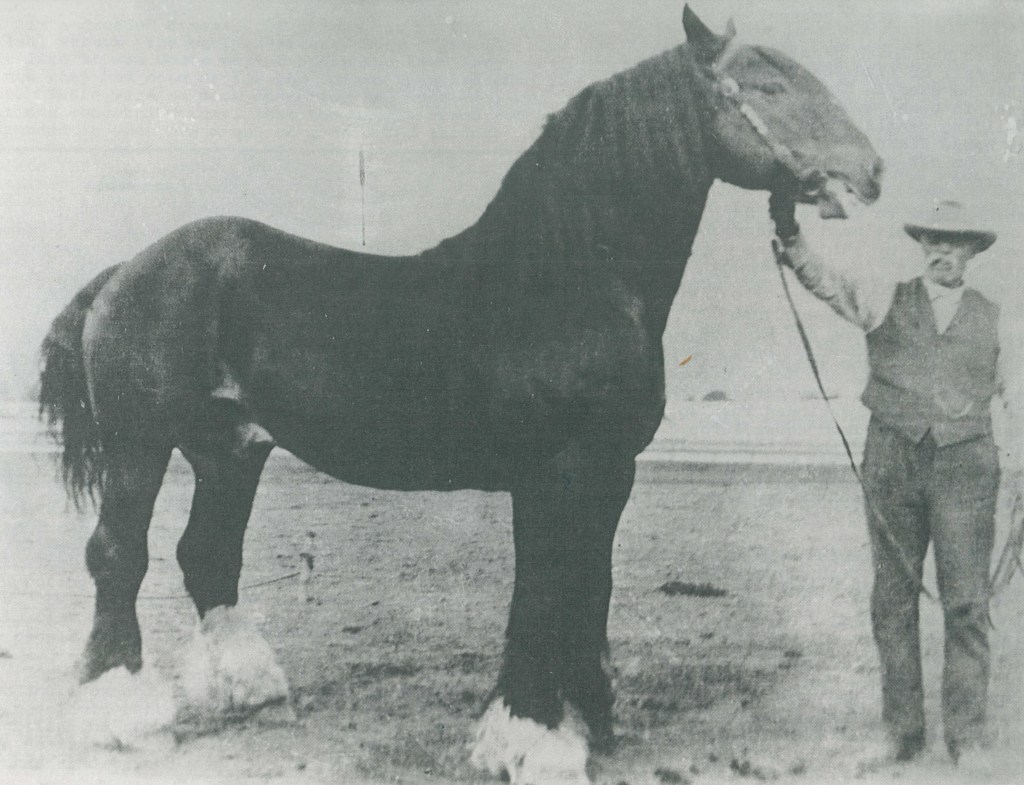

Milo: They lived in Clinton, Sunset. But they run that salt pond and they – – but they had this salt pond out there and they – – they’d harvest the salt. They took the horses out there to use the horses to plow the salt loose so they could harvest it. It used to come in layers after water would evaporate. They take the horses out there, but the horses hoofs would get coated up with salt so bad the horses got so sore they had to bring the horses back out.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: So they rigged up the trucks and tractors and made little tractors and ski-doos to maybe haul maybe a half a ton out at a time – –

Wayne: uh – huh.

Milo: – – without using horses.

Wayne: Did they – – they just sold it in gross weight or did they bag it?

Milo: We bagged a lot of it.

Wayne: Did you?

Milo: 100-pound bags.

Wayne: And you worked out there.

Milo: Oh, I had to work out there.

Wayne: Uh-huh.

Milo: They had a pond – –

Wayne: Did all the other kids?

Milo: The girls never did. Let’s see, Eddie Sharp, Milo’s brother, Eddie Sharp, walked from Promontory across the cutoff to West Weber out here to back to Plain City. He got homesick. He wouldn’t stay out there.

Wayne: He went over on the Lucin cutoff?

Milo: Yeah.

Wayne: How far is that”

Milo: That would be about 75 miles – –

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: – – Going down to Brigham, down around there. But he cut across the railroad track this way. What is it, about 12 miles? Maybe four – – oh, it’d be 12 miles to Little Mountain – –

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: – – Then the cutoff’s be about ten miles.

Wayne: Little Eddie, huh?

Milo: After that – – that’s be Ed Sharp’s young boy.

Wayne: Right.

Milo: But he got homesick and we were working in the salt and Ed Sharp and them guys, see, they was trucking salt over to Brigham and over to Corrine, they was stockpiling it.

Wayne: Oh.

Milo: See, they’d truck pile it in, then they’d go get rations and stuff and come back.

Wayne: Did you stay out – –

Milo: We stated out there.

Wayne: – – overnight:

Milo: They had a big cave back in there. Charlie Carter and them guys had dug their caves. And the Indians had had caves back in that area, Indian caves and stuff back in there, and lived back in these caves for a long time at Promontory. Then they had big tents and stuff that they had out in there. They had the kitchens and stuff out there for the laborers.

Wayne: Right.

Milo: In the wintertime, they had probably ten, 15 guys – –

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: That’s come out with their trucks. They all – – they all bought small trucks and – – they weren’t big trucks, you know, they – – young kids get these trucks and they’d come out there and try to make a dollar.

Wayne: And he loaded them all with this scoop shovel.

Milo: Scooped, everything was scooped.

Wayne: uh-huh.

Milo: No tractor.

Wayne: No.

Milo: It was all shovel. We done a lot of work at nighttime. Nighttime, lot of wok at nighttime.

Wayne: Why? Why nighttime?

Milo: Cool.

Wayne: Oh, yeah. Did that go on the year-round?

Milo: Just in the winter.

Wayne: Just in the winter.

Milo: Uh-huh. Through the winter months.

Wayne: Uh-huh.

Milo: The summertime, see, the – – you could fill your ponds up and then keep – keep your ponds full through the summer.

Wayne: That’s when they make the salt?

Milo: That’s when the evaporation (unintelligible) to salt there.

Wayne: So the winter’s the harvest.

Milo: The harvest.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: But in Promontory, when they put that track across to Promontory, they went across and left a part of the lake with salt and everything in it, deep salt, and Ed Sharp and them harvested a lot of that slat right in there.

Wayne: Uh-huh.

Milo: And one time we was there and it was – – they had this pond of salt and they piled it up to dry, make it white. And the pelicans used to come around. They used to feed them. And they put the dynamite in to blast this salt, and uncle Ed Sharp says, oh, he says, there’s the pelicans. Shoo them away, shoo them away. And they all flew away but one. And he says oh, John, he says, I gotta get you out of there. He ways, gonna blow you up. So Ed Sharp he run back to where the dynamite was and he grabbed this pelican. And he grabbed the pelican and he run, I don’t know how far, not very far when this blast went off, the salt blowing it up. But the – – he fell, fell down on the salt and the bird went away. The birds couldn’t fly because they had salt on their wings. So they’d take these pelicans up and they’d wash them so the pelicans could fly again. But he saved that pelican’s life. But he could have got killed himself.

Wayne: Yeah, I’ll say.

Milo: But I – I’ve often thought about Ed Sharp doing things like that. But he raised me to be a good – –

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: – – Boy.

Wayne: Dad used to love to talk to Ed. We’d sometimes leave here, Grandpa’s place, headed for Warren. But we’d sometimes end up at a – –

Milo: Yeah.

Wayne: – – Ed’s and I would set there on the hay rack waiting for those two people to stop talking.

Milo: Yeah.

Wayne: They really, genuinely liked each other, I think.

Milo: But see, Ed Sharp, he – – he rented ground off of Bill Freestone down in Warren.

Wayne: Oh.

Milo: Where Milton Brown lives, there used to be a house out in the back.

Wayne: Oh, okay.

Milo: And Bill Freestone lived out in the back of there and Ed – –

Wayne: I remember that.

Milo: – – Ed Sharp – – see, I was a kid, we used to go down there and he planted – –

Wayne: Just across the creek from uncle Earl – –

Milo: – – Potatoes and stuff.

Wayne: – – Hadley’s.

Milo: Yeah, down by uncle – – now, where your uncle Earl Hadley and his wife lives, me and Howard Hunt seen that twister that come through the country and tore down the creamery. The old pea vinery.

Wayne: Down on the salt flat or on the – – in the pasture.

Milo: Yeah. Me and Howard Hunt seen that cyclone pick that building up. We was in Howard’s dad’s car. We seen that twister come through the country. And we was kind of watching it, riding through the dirt roads, and we rode over here by the dump road going down to Hadley’s, and that picked that building right up and it twisted it around tight up in the are and twisted it around and then it just set it down and then it crumbled.

Wayne: I remember that.

Milo: And it went right – –

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: And it went right down, this twister went down across the road and then it come back towards your uncle Earl Hadley’s and it come – – missed his house. But it went – – his barn was kind of front and north of the house, and it went right through there and it picked up part of that barn on the west side, it picked that sloping part up. Mr. Hadley and his wife had just come in to have dinner, and they put the horses in there with the harness, hames and that all on – –

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: – – And that picked that shed up and set it back down on them horses. And me and Howard run in there to help Mr. Hadley, we pried that up. Mr. Hadley reached in and talking to them horses and his wife, Liz, I think is her name – –

Wayne: Right.

Milo: – – But each one of them talked to them horses so they didn’t jump around. And me and Howard helped pry that roof up, and he took them horses right our of there. And them horses – – I often thought about that. If nobody was around, see, the horses would have probably died.

Wayne: Yeah. And you were down there working on Ed – –

Milo: No – –

Wayne: (Unintelligible)

Milo: Me and Howard was in the car. He’d borrowed his dad’s car. We was – – we had the water our there by uncle Ed Sharp’s, and Howard said, come and ride down to the store with me. So we go down to buy the ham – – the baloney to make a sandwich.

Wayne: Just down to Olsen’s or Maw’s?

Milo: Maw’s Store.

Wayne: uh-hu.

Milo: And we seen that twister coming.

Wayne: Oh, you – – oh.

Milo: You could hear it.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: You could hear it. And we was startled. We was dumb. We wanted to drive in it.

Wayne: Yeah, you bet.

Milo: If we’d a drove in it, see, it’d a probably picked us up.

Wayne: Yeah. That’s how you got such a good view of it though. You were chasing – – out there chasing it.

Milo: Well, we was watching it.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: But we got to see the creamery – – the vinery go down.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: And we got to see the barn pick up, the lean-to on the west side and then we seen it set – –

Wayne: That’s right.

Milo: We could see the horses.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: And then it set that right back down. And them horses, I guess the rafters and that probably wedged just so that it didn’t kill them, you know.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: Then you see, right after – – right after that, see, we had to go into the war.

Wayne: Right.

Milo: World War Two.

Wayne: I wanna cut back. Taking much more time – – of your time that I meant to. But can you tell me briefly what you know about how Howard got killed in the war?

Milo: Howard – – Howard Hunt, they tell me, got killed by our own ammunition.

Wayne: They were in Italy?

Milo: In Italy.

Wayne: And he was with the Gibson kid and Arnold Rose?

Milo: Also Folkman. I think Folkman was in the – –

Wayne: Oh, I thought he was in Navy.

Milo: I don’t know.

Wayne: Leon?

Milo: They were all close together at that time.

Wayne: Uh-huh.

Milo: Whether they was on the move or what, I don’t know. But Archie Hunt could tell you.

Wayne: Probably – – Archie’s Vic’s son.

Milo: Yeah, grandson.

Wayne: Grandson.

Milo: But he could tell you.

Wayne: Gee, I maybe oughta go see him. Who did he marry?

Milo: He’s remarried Ez Hadley’s wife. Now, you know Harold Hunt?

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: Harold Hunt might be able to tell you about Howard.

Wayne: Yeah, I’m not gonna be able to see Howard. I’m going home tomorrow.

Milo: Are you? I can run you down to Archie Hunt’s. But see I went into the war. Howard went into the war.

Wayne: Right.

Milo: Out of all of us guys from Plain City that went in on the first draft, they sent us down to Fort Douglas, Utah.

Wayne: When did you go in?

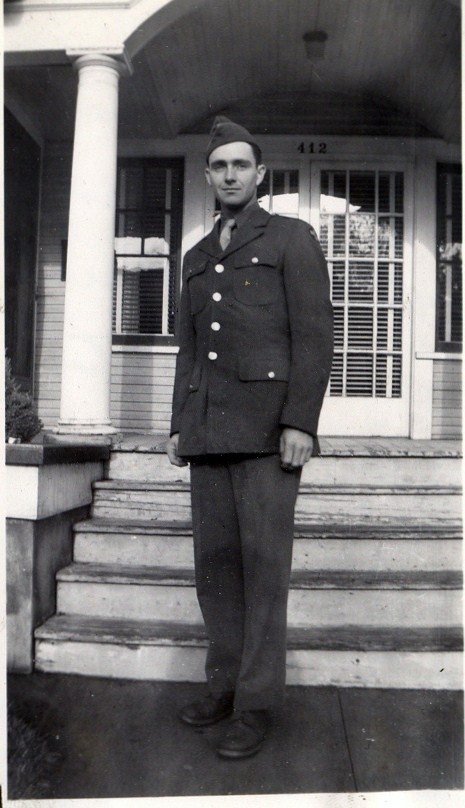

Milo and Gladys Ross, 30 May 1942

Milo: In what was it, ’41? Took us all in town the first draft.

Wayne: Howard went with you?

Milo: No. No, they come in later.

Wayne: Oh.

Milo: But the first draft, they sent us all out, we went out of the Bamberger tracks.

Wayne: Who was with you, remember?

Milo: Ellis Lund.

Wayne: Yeah.

(l-r): Kenneth Barrow, Ellis or Keith Lund, Milo Ross, Jim Jardine, Unknown, Victor Wayment, Earl Collins 16 Oct 1942

Milo: Yeah, Ellis Lund and – – now I’ve lost it. But we all went down to Fort Douglas. We got down to Fort Douglas. They examined us, shoot us, and everything else like that. Put us in barracks. And they called my name our after they examined and tested us on everything, they called my name out to come up the office. I go up to the office. I was supposed to go get my duffel bag, be ready to move out so – – so many minutes. I run back to the barracks, got my bags and everything, and come back up where I was at. They put me in a jeep with four, five other guys. They took us right down to the railroad station in Salt Lake. They shipped us out to Fort Lewis, Washington, the same day, night we got down to Fort Douglas, they shipped us to Fort Lewis, Washington. And I was the only one out of the whole group that was sent out. And the rest of them guys all stayed here a week or two down here to Fort Douglas, Utah and they sent me up to Fort Lewis.

Wayne: You were just at Douglas long enough to get a – –

Milo: Examination.

Wayne: – – Uniform and – –

Milo: Yeah, they hurried me right through.

Wayne: Why?

Milo: I don’t know whether they had a call they wanted so many to go on this troop, Illinois outfit, National Guard outfit coming through, I don’t know.

Wayne: What, so you did basic training at Fort Lewis?

Milo: Yeah.

Wayne: That’s where Norm and Paul – –

Milo: They came there, yeah.

Wayne: uh-huh. For the 41st division.

Milo: Yeah. But they come up a little later.

Wayne: If we’re on your war career, we might as well stay with it, then we can cut back. What else did you do in the war besides go in early and – –

Milo: Well – –

Wayne: – – Get hijacked in Salt Lake?

Milo: Well, here’s the deal. What I was gonna tell you about. They asked us these questions about putting these pins together. If you open a window, how many panes would you have if you opened – – as a window over there, if you open that there window over there halfway, how many panes would you have? You understand it? Like a sliding window?

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: If you opened that there window, how many panes would you have if you opened it halfway? How would the four – – would you have it if you opened it halfway? You understand it?

Wayne: Has that army general intelligence (unintelligible)

Milo: Intelligence stuff.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: And I didn’t care. I was mad. You understand it? I – – I really didn’t care anything about that. And they – – they says, do you like to shoot a gun? And I says I’m – – I’m an expert rifleman. And maybe that there’s why they throwed me out, you know? They didn’t like me down there.

Wayne: This is at Fort Douglas?

Milo: Fort Douglas. And they put me on a train and I went from here right on the – – tight up to Fort Douglas, Utah, and done all my basic training there.

Wayne: Fort Lewis, Washington.

Milo: Fort Lewis, Washington.

Wayne: Uh-huh.

Milo: And I spent my time there, and then after we done our time at Fort Lewis, we went down to Needles, California, Barstow, and opened up a big army training camp down there. We dug great big latrines and trenches and they brought wooden boxes in for toilets and stuff like that.

Wayne: What kind of outfit were you in?

Milo: That was with the 33rd division.

Wayne: In an infantry – –

Milo: National Guard. Illinois National Guard.

Wayne: Oh, okay.

Milo: 33rd, Golden Cross.

Wayne: Okay. Is that you?

Milo: Yeah. I’m a highly-decorated soldier.

Wayne: Yeah, you are.

Milo: Yeah.

Wayne: Well, tell – – let’s stay with that.

Milo: But.

Wayne: tell me about your war.

Milo: We was – –

Gladys: Before he leaves, I’d like you to show him the plaques that you made (unintelligible).

Milo: Okay.

Gladys: (Unintelligible)

Milo: Okay. He can hear you. At Fort Douglas, Utah, they had an air base there also. They had the B-51’s and P-38’s and they were training the pilots and everybody. And we were training there. And they put me in the infantry. And I done a lot of – – lot of latrine duty. We was in barracks.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: Fort Douglas – – Fort Lewis.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: And didn’t matter what I done, the company commander, whoever it was, he liked me. If we go out on maneuvers, rifle shooting, anything like that, they liked me because I could hit the targets. They could pull a target up and I could shoot it.

Wayne: Like Plain City kids, you’d grown up – –

Milo: I done it.

Wayne: Sure.

Milo: If we run infiltration course or anything, get down on your guts and crawl.

Wayne: Uh-huh.

Milo: Go under the barbed wire and this and that – –

Wayne: Right.

Milo: – – I done it. And they liked me. And they – – they come along with the 60- millimeter mortar. Told me all about that, an one thing another. And they said, do you know how far that is down to that tree down there? And I says, yeah, I say, it’s probably about 150 yards. And didn’t matter what they done, they’d fire this mortar, 150 yards, they’d be on their target. You know, I wasn’t doing it. But they was asking me these things.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: And they’d say, how far away is that tree over there. I’d say, well, it’s close to a thousand yards. But I was good on – –

Wayne: Right.

Milo: – – Distance.

Wayne: Uh-huh.

Milo: And it didn’t matter what I done. And as soon I was there, I was the soldier of the month the first month.

Wayne: Wow.

Milo: I got a pass out of it, you know, and then they made me a private first class and then a corporal and then a buck sergeant, you know.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: Then when I got down to Barstow, they made me a Tech Sergeant. Give me a weapons platoon. And that was your 30 machine guns and your 60-millimeter mortars, see? But they give me a platoon down there. And then when they give me the platoon, they put us on guard duty one night. And they took me way out in the desert and left me. Now, you’re gonna stay here until certain hours and then you’ll be relieved. Well, I was gone through the night. The next morning at about noon, here they come to get me. And they said, well, why didn’t you walk in? I said, walk in? Why walk in? I was told to stay here. Was you scared? I had an order. I done it. I get back to camp, they give me a five-day pass for being a soldier of the month down there. You see?

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: So they give me a platoon sergeant. They made me a two-striper. One stripe under at that time.

Wayne: Oh, a staff – –

Milo: Yeah, a staff sergeant.

Wayne: Uh-huh.

Milo: Then. And then they made us a two star later on. Two stripe after.

Wayne: And that’s the tech.

Milo: Tech, yeah. After that. But they was changing at that time. But they give me a five-day pass. And I come back to Utah.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: They give me a five-day pass, but I could only have three because we were shipping out. So I hurried home see my wife, Gladys. She’d come back from Washington so she could be with me just that – – say hello.

Wayne: Uh-huh.

Milo: And I come home to see my wife and I had to go right back the next morning so I’d be able to ship out.

Wayne: You went back to Barstow?

Milo: Barstow.

Wayne: Your outfit was – –

Milo: Barstow.

Wayne: – – Still there.

Milo: We was ready to ship out. But I’d received this five-day pass that had – – soldier of the month award.

Wayne: Yeah.

Milo: So that’s why I got to come home and to go back. So then they – –

Wayne: When had you got married?

Milo: Well, we got married in ’41. See, then – –

Wayne: Just before you went in?

Milo: Just before we went in. And see, I never seen my boy, Milo, he was born while I was overseas. I didn’t see Milo until he was three years old.

Wayne: Uh-huh. Who did you marry?

Milo: Gladys Donaldson.

Wayne: From Ogden?

Milo: Ogden, yeah. Dave Donaldson’s daughter. Dave Donaldson. They lived on – well, Norm, he used to go up there. They used to pick Gladys up. And Frank Hadley, they used to go pick Gladys and their sisters all up. They used to go up there. But they – – they shipped us out of Barstow and they was gonna send us – – they was gonna send us in to Alaska. They give us all this here heavy equipment and everything, go to Alaska. Then when we get on the ships, the first thing the do is give us new clothing and everything, and we’re going to the southwest pacific. So we went into the Hawaiian Islands. So that’s where – – where we started out at, Hawaiian Islands.

Wayne: Right.

Milo: Then we went from Hawaiian Islands down through – – down Past Kanton Island, Christmas Island, Fiji Islands. We was gonna go into Australia, then they decided instead of going into Australia, they had kept the Japs from going into Australia, so they sent us back up into the Coral Sea, back up into New Guinea.

Wayne: Yeah.